Luxury for tourists, lockdown for locals

by Mushfiq Mohamed

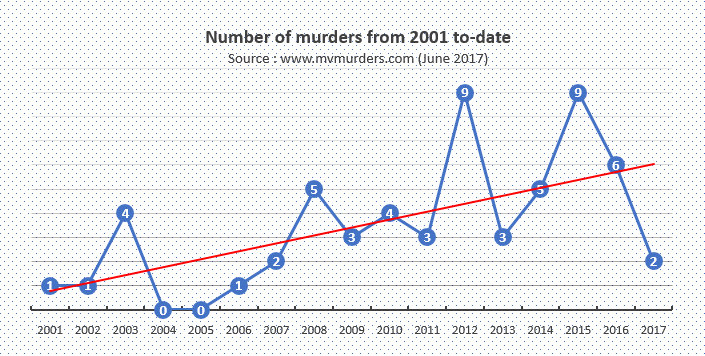

The number of COVID-19 related deaths in the Maldives have surpassed the number of Maldivian fatalities from the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.

Yet the Maldivian government efforts to generate tourism revenue equivalent to pre-COVID19 levels are lending to the spread of the new variant of the lethal coronavirus in the island country. On Thursday it recorded a coronavirus related case of black fungus or Mucormycosis. This petrifying case, and the surge in COVID19 fatalities, coincide with increasing coronavirus cases in India and the rest of South Asia. The country is bracing itself for yet another national lockdown.

Leaked images show that the Maldives has been offering stranded tourists “quarantine packages” to kill time in the islands before moving to their destination. Bollywood actors and athletes have also chosen the country as their site of reprieve from the pandemic, as if Maldives were immune to the unfolding global health crisis.

Although the country’s famous tourist resorts are on private islands, most of its staff are local. In a sense, held captive in substandard accommodation without the ability to freely travel to their families on local islands, a fact further exacerbated by the COVID-19 restrictions. Social media posts showed photos of squalid staff quarters in world-renowned five-star hotels. Nevertheless, the mainstream media continually centres on the ‘plight’ of stranded Western tourists, never highlighting the unacceptable situation of the unobtrusive local workers who manpower the luxe-tourism industry.

The Maldives’ tourism market represents the ether of high-end indulgence. The tourist resorts look like elysian spaceships that have beamed down on desert islands scattered in the Arabian Sea, divinely assembled for its visitors. Underwater wine cellars and restaurants that boast Michelin-star chefs. Overwater villas with rooftop waterslides that vortex you into the turquoise sea underneath.

The ownership and enjoyment of the Maldives’ natural beauty are swiftly slipping away from the hands of ordinary Maldivians.

It took us Maldivians a long time to realise that there existed an apartheid system between the flourishing elite in Male’, and the people from the outer atolls that were historically deprived from having a stake in the country’s economy. Only the industrious middle-class (from the islands and Male’) and some of the descendants of landed nobility (concentrated in the capital) bag influential chunks of the industry that brings in 60% of foreign income. It is also true that most of this money is never really injected into the local economy, it vanishes into bank accounts in offshore tax havens owned by the global hospitality industry oligarchs.

In 2019, Maldives had 1.7 million tourists. The Tourism Ministry’s figures show that the pandemic gutted the 5-billion-dollar local economy in March 2020, and it has not recovered since. Despite this, in late 2019 and in the last few months this year, the government found creative ways to revive it at the expense of the Maldivian people.

Pandemic profiteering

Maldives was one of the first countries to open for tourism after lockdowns globally, at a time when the pandemic was raging in Europe, which includes the top-10 countries whose nationals frequent the island nation. Tourists were exempt from the lockdown measures, restricting inter-island travel only for locals. Male’ especially was closed down possibly due to its proximity to the country’s busy international airport in Hulhule’.

Negative PCR tests are required since October 2020 but when the pandemic was at its worst in Europe and North America last year in July, guests were flowing in and weren’t required a negative test. The borders were open without any test or tracing procedures.

A tone-deaf Forbes article mentioned that the Maldives was “desperate” enough to fork out its vaccines for visitors. It was also an article that centres multinational corporations, eliciting criticism over how these companies are twisting the arms of a poor country. A premature announcement by the Tourism Ministry that had no word of the public health officials or the Maldivian people.

Within the industry, lockdown restrictions discriminated against guesthouse tourism. In April, when India was recording unprecedented COVID-19 related fatalities, the government only shut its doors on Indian guests seeking to holiday on inhabited islands. Meaning affluent Bollywood stars could still have their Maldives’ escapades if they can afford to go to a private resort island (considered ‘uninhabited’ islands). Small businesses are routinely bearing the brunt of discriminatory lockdown measures.

The government announced lockdown measures early this month for locals. But the borders remained open. After the HPA demanded the borders be closed for South Asian tourists, the government finally stopped issuing tourist visas on 13 May, in the same breath reassuring that these measures will be reviewed later this month.

None of this prevented Australian cricketers stranded in India from quarantining in the Maldives before heading back down under. In the same way that the government allowed Asian Football Federation (AFC) to send football teams to the Maldives for an AFC Cup playoff match between Bengaluru FC and Eagles FC. It was only when Maldivian social media users began criticising the move, amid circulating photos of players strolling around Male’, in breach of restrictions, that the youth minister cancelled the planned AFC matches.

Bollywood in the Maldives

This year, as corpses piled up abandoned in Indian cities, the country’s elite decided it was time for a change of scenery. While the virus was completely devastating South Asian cities, Maldives was hosting Bollywood actors in a bid to resuscitate the tourism-dependent-economy. The move backfired in both countries, with many shaming the celebrities for their lack of conscience during a once-in-a-century pandemic.

‘The Sunny Side of Life’ felt like an awkward choice for Bollywood, an industry plagued with colorism. It was purely status-signalling. Indian social media conversations on the Maldives are fascinating. Some suggest the Maldives belongs to the Indian Ocean, and is therefore part of India. There was little reflection over Maldivians’ cultural and linguistic affinity to India – the focus was on marking territory. On their Instagram accounts, the location indicates the Indian Ocean. In the captions, they marvelled over the glimmering seas that form their ‘backyard’, which some could not even bring to name or locate.

Ventilator corruption

Last year the government was embroiled in a corruption scandal worth over MVR30 million (USD 1.9 million) involving ventilators that were unlawfully procured from a Dubai-based company.

This initially slipped the radar of the anti-graft body, which later found that the former health minister and 11 employees benefited from the scam violating local public finance laws.

A year later, the embattled government is nowhere close to reclaiming state funds lost to yet another massive corruption scandal.

The less luxurious side

According to the Reuters vaccine tracker, around 42.9% of the country’s population have received the first dose of the vaccine, including some 90% of frontline workers, consisting of tourism staff. Tourist workers, and others who depend on the industry have suffered the most during the pandemic. Tourism Employees Association reported approximately 25,000 tourism employees have been laid-off within the past two years.

When the pandemic hit the Maldives last year, South Asian migrants working in the frontlines were the first to be adversely affected. Many were trapped in congested accommodation without pay and the means to return home. Those who protested forced unpaid labour were quickly arbitrarily deported without awarding damages. Many news outlets ran xenophobic headlines blaming impoverished Bangladeshi, Nepali and Indian workers for ‘spreading the virus’.

In this way the pandemic has exposed the existing structural inequalities in Maldivian society. If you are a politician or a businessman, there are no COVID-19 rules that get in the way of what you want. None of these Big Men suffered the consequences of breaking the rules; fines for violating restrictions were ironically deployed against those who cannot afford to pay it.

Whether it is campaigning and holding local council elections or opening the country up for luxury tourism as the numbers skyrocketed, the consequences have trapped the locals in with the new variants of a dangerous disease in a country whose capital city’s congestion levels rival Hong Kong and Manhattan.

Conclusion

As the Tourism Minister promises endless vaccines, the reality is a lot more finite. It seemed like yesterday when India was the exemplar of COVID-kindness, generously donating vaccines. Today, the Indian government’s feckless response to the catastrophe has been rightly described as a ‘crime against humanity.’

Indeed, the Maldives’ tourism industry does not want its wealthy tourists to be troubled by the inconvenient existence of a local population. The seemingly innocuous imagery invoked by the 3-billion-dollar industry cannot be divorced from the structural violence it regularly detonates against ordinary Maldivians.

Perhaps we are to be blamed too, for popularising the image of the Maldives as blank-slate beaches awaiting consumption by the West, and more recently the United Arab Emirates, Brazil, India, and China.

“No news, no shoes” reads a tagline of a resort where tourists spend millions per night. The world, and all the chaos within it, happen elsewhere. A proliferated untruth that costs ordinary Maldivians the chance to live a life in dignity. It is an industry that relegates locals to second class citizenship through a structure that is displacing and killing Maldivians, concurrently making the Maldives’ vulnerable eco-system uninhabitable.