Starved for justice: the Rilwan & Yameen story

by Mushfiq Mohamed

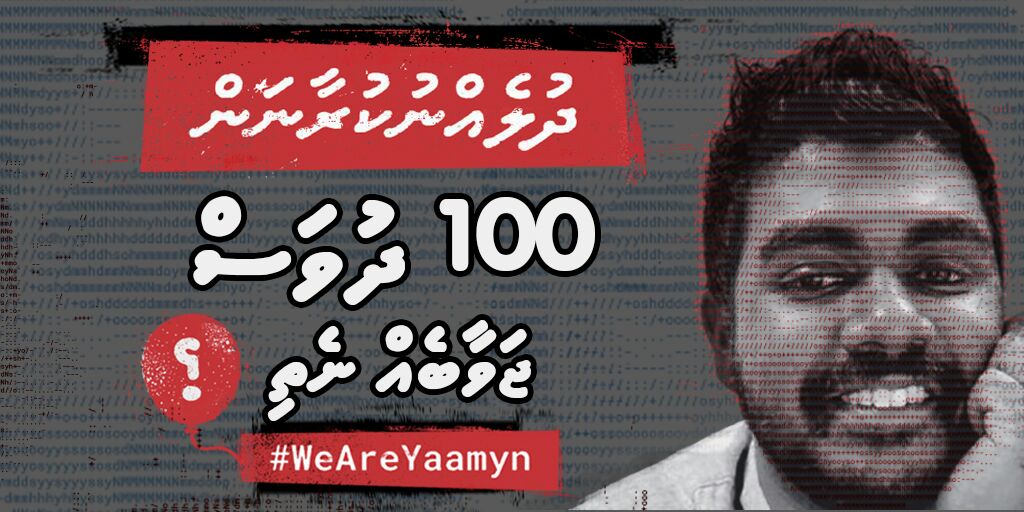

Rilwan and Yameen were peaceful, principled and brave. Their calming presence, wit and humility set them apart from the average modern Maldivian. Even as I write, I think of a multitude of cheeky comments Yameen would have made about how carefully I frame my words. The principles they believed in were clear, simple and open. The aspirations and values they had for the society into which they were born should not be controversial to anyone. Many mistakenly think Yameen and Rilwan only wrote about religious extremists. Their focus was not so narrow. On numerous occasions they wrote beautifully of how society was rotting at its core in relentless cycles of nepotism and political violence, causing the kind of cultural decay and malaise that requires persistent resistance. It would take a continuous and infinite revolution to resolve. The Maldives may have interrupted these two incredible souls, but their soul-searching over our nation’s condition continues to resonate with many of us.

The last time I spoke to Yameen, he was here in London in March 2017 after winning seed funding from a global tech company for a breakthrough healthcare app he developed. We could not meet but planned to catchup in Malé when I went back to renew my visa. A few days after I returned to Malé in April, I woke up to the horrific news of his killing. In contrast to our planned laughter-filled interaction, I went to his funeral in April 2017—filled with echoes of his family’s cries.

Why do we keep speaking of Rilwan and Yameen? Why not stay quiet and let the government attend to its ‘more important tasks at hand’? Why not focus on the issues of bread and butter? Why not talk of the sewage systems some island communities are still waiting for? Or the privatised healthcare system? Or the fact that clean drinking water is still a privilege on several of these islands? It is because you cannot talk about bread without talking about the blood on the streets. Those crime scenes might have been hosed down, the evidence erased or negligently abandoned. But the loss of these two promising young men is forever imprinted in the minds of their family and friends, and the young people of this nation.

It is a waking nightmare to call home a place where my friends could disappear by force or brutally hacked to death in their own homes as they would in a lawless failed state.

What is most devastating is the deafening silence of the masses, a majority of whom appear conditioned into questioning the powerless over the powerful. It surely should be the other way around. The Zeus-like politicians with their entourage of yes-men, who can be capricious and populist while promoting democracy, do not realise still that their inaction and shifting priorities will eventually extinguish the small flames of hope the Maldives had for an open society that legally recognised and protected all Maldivians equally.

DDCom

“The knife you see in this picture was found on the road outside Rilwan’s apartment [building] on 7 August 2014 after an individual was seen being forced into a car”

Deaths and Disappearances Commission (DDCom), 8 February 2021

For years, Rilwan’s family and friends talked about the knife, the red car, the abduction. In the end they killed the most vocal critic of police negligence in investigating Rilwan’s abduction and its connections to Salafi-Jihadism. Yameen refused to stop questioning until they silenced him literally. Others who joined the family in their campaign for justice were followed and threatened in full view of CCTV cameras. Plots were hatched to kill us. In September 2014, one of the men implicated in the abduction of Rilwan threatened to disappear me too. He did so openly, on a street of Malé. Leevan Shareef was cornered and quizzed on his Islamic knowledge the next year. We were subject to hostile surveillance again in late 2016. Our police reports gathered dust without so much as a statement from Leevan and I. When Rilwan was abducted and Yameen was killed, records of death threats against them, ignored by the police, went as far back as ten years.

The new government set DDCom up with the pledge to resolve the atrocious crimes of the past, including those committed by the previous government. Transitional justice, they proclaimed, was an important cause for this government. In April 2019, for the first time, the president joined the third rally held to commemorate Yameen’s killing. President Solih seemed to have a lump in his throat as he spoke of the importance of serving justice for Rilwan and Yameen’s families. Activists reminded the government that we may never have another opportunity to get to the truth. These cases are but just two of the 27 cases the DDCom is attempting to resolve since it was formed in 2018.

What is the actual state of justice for these families behind the circus of presidential commissions and newly enacted transitional justice laws that seem to do nothing more than enable political mudslinging?

Speaking to the media in April 2017, weeks after his 29-year-old son Yameen was killed by vigilantes, his father Hussein Rasheed had to speak words no parent would ever want to. His son’s throat had been cut, he said. “He’d been stabbed in 34 places.” Tears streamed down his cheeks from behind his thick black spectacles as he continued, “A part of his skull was missing.” Without a care for the sentiments of the grieving family, social media went into overdrive. Some cruelly shared leaked police photos of Yameen’s mutilated body. Opposition politicians (who now hold power after the 2018 elections) joined the chorus of condemnation against the killing.

Fast forward to today, there are institutions mandated to serve justice and provide reparations and closure for these families who have had their lives put to the test. This is worthy of praise but meaningless if it is incapable of putting perpetrators behind bars. The main objective of such commissions is to prevent any chance of atrocities recurring. The present reality elucidates that their cases were steppingstones for Maldivian political animals who now conveniently promote the status quo after winning the vote and cushy new positions.

The trials

Months after Yameen’s murder, the previous government was quick to prosecute the alleged killers. The hearings continued at lightning speed. One thing that came to my mind was: why is this a murder trial when the crime was an act of terrorism? If Rilwan’s alleged abductors were accused of terrorism, why aren’t the perpetrators of Yameen’s extrajudicial killing seen as terrorists who planned and executed someone based on perceived ideological grounds? The planning of the assassination took place in mosques in Malé. When this information became public through the reporting of the trial, Maldives Twitter protested that a place of worship was being sullied over this murder. They did not find it offensive that the sanctimonious surroundings were used to plot a cold-blooded killing of a person.

Eight individuals were suspected of killing Yameen. Six were charged and pleaded not guilty to murder. Prosecutors declined to press charges against the other two, including one who was initially accused of aiding and abetting. Perhaps giving a clue as to the possible plea bargaining that had gone on behind the scenes before the case reached the courtroom.

For two years, since the trial began in 2017, activists had to pressure the previous government’s chief prosecutor to hold the hearings in open court. His family were repeatedly prevented from entering the courtroom, and the hearings were subject to regular cancellations. Exasperating the family still processing that their beloved had been ruthlessly slaughtered, and the plotters, enablers and active executors hid in plain sight. Almost all the hearings in 2018 were held in secrecy until July that year, despite growing calls to end the closed-door charades and open the trial.

Then in November 2018, to the shock of many locals and observers alike, President Abdulla Yameen’s government lost the presidential election to the ruling party, Maldivian Democratic Party’s President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih, leading a coalition consisting of defectors, dictator-loyalists and Islamists. The mix, politicians decided, would produce national unity after a long period of political turbulence that began in late 2011. Regardless of competing interests within the government, justice for past abuses was said to be prioritised. In 2019, defence lawyers began using delaying tactics to slow down and manipulate the judicial process. The State, too, was accused of failing to produce witnesses or defendants in time for the hearings. Prosecutors eked out excuses for delays, clueless as to why it was being stalled.

“Those who organised and financed Rilwan’s abduction and Yameen’s murder,” the DDCom chair disclosed, “are the same.” This whirlwind of revelations was made in September 2019. It was even more precarious than that. Acknowledging publicly for the first time, the chair also confirmed that it was “local Al-Qaeda affiliates” that carried out these crimes, including the murder of an Islamic scholar and politician, Dr Afrasheem Ali, known for his relatively less conservative views on Islam that clashed with the fundamentalist positions held by more politically influential scholars and religious leaders.

In late 2019, prosecutors complained in court that their witnesses were subject to undue influence, without making any direct accusations against the alleged perpetrators or their lawyers. The courtroom was dominated by the defence lawyers whose presence outsized the judge and the prosecution.

When the COVID-19 pandemic took over the world, the Criminal Court stopped scheduling hearings for the murder trial. Maldivian courts adjusted to the ‘new normal’ of COVID, switching to online hearings. The murder trial of Yameen, however, remained unheard throughout 2020. On 7 February 2021, the trial resumed after a hiatus of over a year. The new hearings bear the same characteristics as before: delay tactics from defence lawyers, prosecutorial mishaps and judges rendered incapable of administering the trial.

Yameen’s family urged the Prosecutor General to intervene, reminded of how Rilwan’s abductors were acquitted in August 2018, a few days before the third anniversary of his forced disappearance in 2014. There was just a month left before the presidential elections that would shift political dynamics in favour of the opposition coalition. President Abdulla Yameen had to tie up loose ends, fearing his government could be implicated in colluding with the terrorists who assassinated Dr Afrasheem Ali, disappeared Ahmed Rilwan forcefully, and murdered Yameen Rasheed on the same Jihadist ideological grounds.

In his judgement acquitting Rilwan’s alleged abductors, the presiding judge, Adam Arif, blamed the police and prosecution for the incomplete investigation that enabled perpetrators to evade justice. The judge made it clear, in his damning verdict, that the state wilfully ignored credible leads and jettisoned basic procedures, giving way to the manipulation of the course of justice. As the government changed from blatant autocracy to a seeming democracy, prosecutors repeatedly promised Rilwan’s family that they would be appealing the acquittal. Yet, the appeal period elapsed, and nothing moved ahead as promised. A new or re-trial after the DDCom investigation also remains a promise.

Conclusions

The new government was praised for its forthright stance on human rights even before it had done any constructive work, purely based on its aspirations to strengthen democracy after another period of autocratic reversal. The slow-moving pace of justice and fast-moving injustices continue and dampen any hope of holding perpetrators to account. Indeed, perpetrators include those who were in political office then that directly derailed the investigation; not just the radicalised individuals who carried out the acts of religious violence and persecution.

Although the families may not experience finality for these horrific crimes, the only hope is that at least the findings of the DDCom will bring them closure. It must strive to do that before politics becomes turbulent ahead of the 2024 elections. Although none of these trials, investigations or even reparations compare to having Afrasheem, Rilwan and Yameen with us. At times, engaging with this farce appears like a perpetual re-victimisation for these families seeking justice.

Sectarian violence might have been unheard of in the Maldives, but since 2008 and the birth of democracy, with its abuse, the most ardent enemies of liberty have been able to co-opt the benefits of the newfound freedoms. Why would ‘liberal democrats’ give credence to movements that want nothing but their complete destruction? Maldivians nostalgic for an open society can dream but we are stunted by the grief of losing these heroes who spoke out against violence and cultural erasure disguised as religion. Our syncretic and romanticised past, just that, “a mockery of the present” as the brave Yameen Rasheed said.