Migrant workers’ voice: illegal and silenced in the Maldives

by Mushfique Mohamed

As news of socio-political turmoil forces the world to shift its eyes away from the pristine beaches of its beautiful tropical islands, Maldives is losing its untainted image as a luxury tourist destination with more exposure of its appalling track record on human rights. This article looks closely at the lack of both compassion and adequate law enforcement in the Maldivian society’s (mis)treatment of the South Asian expatriate community. It highlights not just the plight of the many Bangladeshi labourers but also the increasing number of South Asian women who are becoming victims of the corrupt and prejudiced criminal justice system of the country.

In addition to the Maldivian population of approximately 330,000, there are 200,000 expatriate workers living in the country, of which a quarter does not have legal status in the country. The Maldives’ treatment of migrant workers is degrading enough for it to be called ‘modern-day slavery.’ The trade generates over US$ 123 million in illegal profits in the Maldives. Last week two Bangladeshi workers, Shaheen Mia and Kazi Bilal were brutally killed bringing to the fore, in tragic circumstances, the unheard voice of the subaltern in today’s Maldivian society.

The government on 25 March banned a planned protest against the deplorable treatment faced by expatriate workers. The protest was planned to highlight the resurgence in violent crime against the South Asian workers. The government of current President Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom’s brother; Asia’s longest serving leader until August 2008, Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, also criminalised a planned protest following similar racially motivated assaults in August 2007, threatening expatriates with deportation.

In addition to silencing their voices and denying them agency, the criminal justice system, primarily the Criminal Court and law enforcement authorities perpetuate injustices against the marginalised. The violation of their fundamental rights is facilitated through certain judicial actors who are untrained, uneducated and corrupt. These judges do not pay any attention to the Constitution or domestic laws or international legal instruments the Maldives has ratified. Increasingly women are becoming victims of the system.

Malékalyanam: buying brides

An Indian woman was arrested night before last on allegations of infanticide and attempted suicide, raising concerns that she could be subject to the same judicial torture as Rubeena Buruhanudeen who was kept under pre-trial detention for over four years. The New Indian Express reported that Rubeena was part of a procedure known in India as ‘Malékalyanam’ in which impoverished girls from the Indian state of Kerala are married off to Maldivian men. Rubeena, married off to a Maldivian man under this procedure, ended up in pre-trial detention in the Maldives for over four years, accused of killing the child she had with her Maldivian husband.

An Indian woman was arrested night before last on allegations of infanticide and attempted suicide, raising concerns that she could be subject to the same judicial torture as Rubeena Buruhanudeen who was kept under pre-trial detention for over four years. The New Indian Express reported that Rubeena was part of a procedure known in India as ‘Malékalyanam’ in which impoverished girls from the Indian state of Kerala are married off to Maldivian men. Rubeena, married off to a Maldivian man under this procedure, ended up in pre-trial detention in the Maldives for over four years, accused of killing the child she had with her Maldivian husband.

Fareesha Abdulla, a Maldivian lawyer who took the case in 2012 on a pro-bono basis, emphasised that the investigation and remand hearings were not conducted with interpreters. “She [Rubeena] can’t understand Dhivehi, but the entire investigation was carried out without an interpreter. Maldives’ police wrote down a statement in Dhivehi and she signed it,” said the defence lawyer. “Infanticide is a serious allegation but when she requested legal aid before I took on the case, the Attorney General denied it,” Fareesha Abdulla explained further.

Before Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi came to power, the Manmohan Singh government’s Minister for External Affairs also urged Maldives to repatriate such detainees. Modi was scheduled to visit the Maldives last month but with international concerns growing over the arrest of former President Mohamed Nasheed on 23 February 2015, took the Maldives off his tour of Indian Ocean island nations. Soon after the diplomatic brushoff, Rubeena was repatriated to India in early March.

Aminath Zara, a Nepalese woman who was fighting for custody of her child with a Maldivian succeeded only after a yearlong legal battle at the Family Court. Zara arrived in the Maldives initially in October 2009 as Tasi Telisa to work at a beauty salon as a beauty therapist. She converted to Islam in 2010. She then left the country in September 2011 and returned after marrying a Maldivian in Sri Lanka in December 2011. When the baby was three, her husband demanded Zara to go back to work; she was the sole breadwinner at times. According to Zara, the marriage came to an end due to her husband’s infidelity while she was away working.

The couple filed for a divorce at the Guraidhoo Magistrate Court in September 2013, but the proceedings and documents were all in Dhivehi, and an interpreter was not offered. The magistrate decided “disobedience” by the wife was sufficient grounds for divorce. As a result Zara became a homeless – and soon to be illegal – single mother. She filed a complaint at the Gender Ministry because her ex-husband was threatening to deport her and gain full custody of the baby. A Maldivian lawyer, Lua Shaheer, who was providing pro-bono legal assistance, said that Zara’s husband repeatedly told her “you are a foreigner, you will have no choice but to leave this country without the child.”

The Gender Ministry provided Zara with temporary accommodation for three months. At the end of the three months she moved back to the island of Guradhoo but could not stand the abuse she was subjected to. With nowhere to live, her former lawyer Lua Shaheer took Zara in to her own home. She is now represented by another lawyer, Fathmath Sama, whose firm took the case on pro-bono.

The husband was represented by Ibrahim Riza, an MP for Gayoom’s Progressive Party of Maldives. The main argument in court was that “the mother is a Buddhist, the mother’s family is Buddhist, and the child would be deprived of a Muslim upbringing.” Zara’s husband also accused her of “abandoning the baby for monetary greed.” Shaheer testified in court that Zara is a practicing Muslim. Even though Zara won custody, the verdict states she cannot leave the country without the ex-husband’s permission if she decides to leave with the baby, effectively leaving her stranded in the Maldives without a place to live.

According to the Indian High Commission in the Maldives, an Indian woman named Manyama Orsu was charged with pre-marital sex and abortion. According to the new penal code, abortions after 120 days of pregnancy are illegal, but a pregnancy caused by rape is an exception to the 120-day rule. Orsu was charged before the new penal code came into effect. The court proceedings against her went on for two and a half years. She confessed to the first charge, and the State dropped abortion charges bringing an end to her arbitrary detention, facilitating her repatriation in late March this year.

There are also reports of other foreign women held at Dhoonidhoo Island Detention Centre on allegations of prostitution, abortion and drug trafficking. Some of these women are victims of sex trafficking and trafficking in persons. But without a systematic mechanism to identify victims, or the mentality to view such individuals as victims, Maldives’ authorities exacerbate psychological and physical trauma suffered by human trafficking victims.

There are also reports of other foreign women held at Dhoonidhoo Island Detention Centre on allegations of prostitution, abortion and drug trafficking. Some of these women are victims of sex trafficking and trafficking in persons. But without a systematic mechanism to identify victims, or the mentality to view such individuals as victims, Maldives’ authorities exacerbate psychological and physical trauma suffered by human trafficking victims.

Two foreign women identified by police as sex trafficking victims in 2008 were provided temporary shelter before being repatriated with the help of their home country’s diplomatic mission in the capital Malé. Due to the lack of investigative infrastructure based on the problem of Trafficking in Persons, nobody was prosecuted for the crime, and the case was dropped due to “lack of evidence.”

Lack of infrastructure & lack of will

There are other instances where lack of legislation, and lack of enforcement, have hindered any efforts to tackle the problem. In 2009, a Bangladeshi man was chained inside a small room for weeks; the chains were removed only when the man was put to work. The employer was released after merely four months’ imprisonment due to lack of anti-trafficking legislation at the time.

The Maldives’ government passed anti-trafficking legislation only in 2013, motivated only by the fear of threatened international sanctions. The Bill had been in Majlis since 2011. However, expatriate workers from South Asian countries continue to be victimized under forced labour conditions notwithstanding the legislation. The US State Department’s Report on Trafficking in Persons states that ‘the [Maldivian] government does not have procedures in place to identify victims of human trafficking.’ As a result trafficked persons are further victimized by the corrupt criminal justice system. At the same time, the legal system remains highly inaccessible to foreigners, especially in relation to criminal law.

Transparency International’s local chapter provided over 560 expatriate workers with legal aid in 2014, mostly with regard to cases that consist of forced labour indicators. ‘We believe that migrant workers are the most vulnerable community in the Maldives today, they do not have access to the legal system due to the language barrier,’ Transparency Maldives’ Senior Project Coordinator for its Advocacy and Legal Advice Centre, Ahid Rasheed, has said.

‘Maldivian society in general views Bangladeshi expatriates as lower class non-citizens; harassment against them has been completely normalized. The authorities view them as the problem and not victims of discriminatory attacks and human trafficking offences.’ Highlighting a history of institutionalised xenophobia, Rasheed said ‘the latest word from the government we heard – regarding the protest – questions basic rights afforded to migrant workers, similar to how all previous governments neglected migrant workers’ grievances.’

The Maldives enacted the Employment Act in 2008, and as a Member State of the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the Act harmonises domestic law of the Maldives with the principles and standards prescribed by the organisation. Independent institutions such as the Employment Tribunal and Labour Relations Authority were established through this Act. ‘Forced labour’ is prohibited and broadly defined to be any instance where there are elements of undue influence, threat, or intimidation with regards to employment. The Act also addresses discrimination at the work place and ensures both local and foreign employees right to freedom from discrimination based on race, religion, social standing, political beliefs, marital status, gender, or family obligations.

It is a common misconception that ‘human trafficking’ or ‘trafficking in persons’ requires illegal entry, similar to ‘human smuggling.’ Human trafficking sometimes begins as smuggling, can end up as exploitation and trafficking, but not all trafficking involves crossing-borders.The United Nations (UN) defines ‘trafficking in persons’ as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation or the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) Convention on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Women and Children for Prostitution was ratified by the Maldives in May 2003; a legal instrument recognizing the importance of establishing effective regional cooperation for preventing trafficking for prostitution and for investigation, detection, interdiction, prosecution, and punishment of those responsible for such trafficking.

The ILO defines the following as elements of forced labour: withholding payment and identity documents; abusive working and living conditions; debt bondage; restriction of movement; excessive overtime; deception; isolation; physical and sexual violence; and intimidation and threats. All of which are daily grievances faced by most low-skilled expatriate workers in the Maldives.

A report by the Human Rights Commission of the Maldives (HRCM) in February 2009[8] states that Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan and Indian nationals are detained at the Malé Immigration Detention Center, managed by the Expatriate Monitoring Center under the Department of Immigration and Emigration. Ordinarily detained for not holding a valid passport, visa or work permit. HRCM urged the Maldives to become a member of the International Convention on the Rights of All Migrant Workers (ICRMW). The national human rights committee’s report recommended development and implementation of systematic procedures for government officials to identify victims of trafficking among vulnerable groups such as undocumented migrants and women in prostitution, who are human trafficking victims. It also urged identified victims of trafficking to be provided necessary assistance and not be penalized for unlawful acts committed as a direct result of them being trafficked.

The US State Department has consistently raised the issue of increasing debt bondage among South Asian migrant workers under its annual Trafficking in Persons report. According to its most recent report, migrant workers pay agents around US$2,000-4,000 to work in the Maldives. There have been reports that some of the 200 registered agents bring migrant workers to the Maldives under terms of employment that amount to criminal acts of deception or fraud, entangling employees in a vicious cycle of debt. The report also recommends that Maldives accede to the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons.

The US State Department has consistently raised the issue of increasing debt bondage among South Asian migrant workers under its annual Trafficking in Persons report. According to its most recent report, migrant workers pay agents around US$2,000-4,000 to work in the Maldives. There have been reports that some of the 200 registered agents bring migrant workers to the Maldives under terms of employment that amount to criminal acts of deception or fraud, entangling employees in a vicious cycle of debt. The report also recommends that Maldives accede to the UN Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons.

The government has failed at implementing enacted laws, and it appears to be using the rise in violent crime to militarize the police service, and enact legislations that strip away the protections, freedoms and liberties enshrined under the Constitution that introduced democratization to the Maldives. As the focus remains on suppressing dissent from citizens who oppose the regime, the plight of the subaltern stays at the political periphery. The Maldives has yet to fulfill the minimum standards required to eliminate human trafficking.

Human trafficking victims are regularly penalized for acts that are the result of being trafficked; excluded from the legal system; and viewed as offenders. Maldivian authorities are known to detain such victims under inhumane conditions. The real perpetrators of trafficking such as employers, officials, recruitment agents or firms are rarely brought to justice, giving full impunity to these powerful offenders who have connections to transnational organized crime. The insularity observed among majority of Maldivians is reinforced on an institutional level by denying inalienable rights that are to be afforded to all citizens and non-citizens indiscriminately. Sex trafficking, forced labour, debt bondage and other forms of exploitation do not end with enacting legislations or acceding to treaties in order to be accepted as a member of the international community. A stipulation under law is only powerful to the extent to which it is realized, and for the subaltern – without the qualification to even speak – those rights are continually denied.

Mushfique Mohamed is a practising lawyer at Hisaan, Riffath & Co., and also works as a consultant for Maldivian Democracy Network.

Main Photo: primecollective.com, Rubeena Buruhanudeen, Minivan News

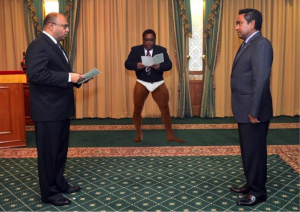

The vote was won and, Sunday afternoon, it was reported that JSC had proposed Supreme Court Justice Abdulla Saeed for the post of Chief Justice. Sunday evening, Parliament was back in session and Abdulla Saeed was appointed the new Chief Justice with 55 votes. Before midnight, Abdulla Saeed had taken oath.

The vote was won and, Sunday afternoon, it was reported that JSC had proposed Supreme Court Justice Abdulla Saeed for the post of Chief Justice. Sunday evening, Parliament was back in session and Abdulla Saeed was appointed the new Chief Justice with 55 votes. Before midnight, Abdulla Saeed had taken oath.