Maldives: Ecocide as Achievement

Humay Abdulghafoor

On 15 March 2023, fireworks and led lights lit up a site of state sponsored ecocide in the southernmost tip of Gaaf Dhaal atoll in the Maldives, as President Solih celebrated another destructive airport project.

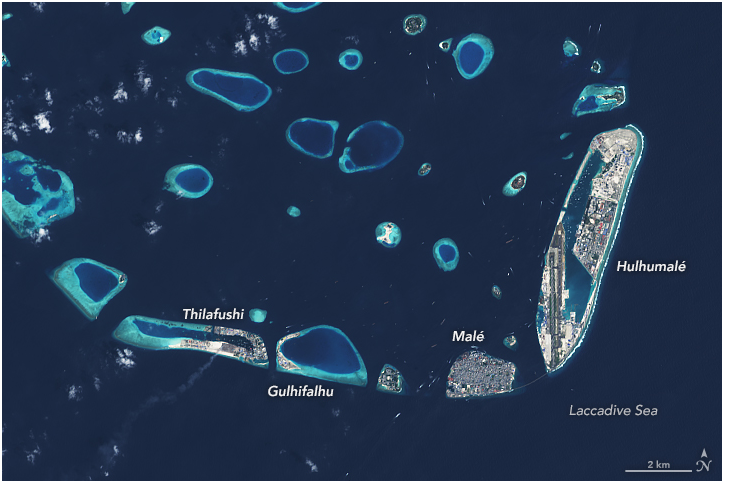

Holding pole position on the victim-list of global climate change, Maldives pleads shamelessly for global climate funds. It also expects to blamelessly destroy finite natural ecosystems and climate change defences for short-term political expediency, and claim from the international taxpayer to ‘mitigate’ willful ecocide. The government of Maldives is well aware of the imminent and unknowable impacts of global climate heating to its natural foundations, which constitute the seventh largest coral system in the world. The country’s finite ecosystems including coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangroves, wetlands and the rich and yet to be studied biodiversity within, sustains the nation’s economic lifelines – its tourism and fishing industries. The Maldives State of the Environment Report 2016 says that 98% of the country’s exports and 71% of its employment are directly linked to its biodiversity sector. This is unsurprising in a nation constituting 99% ocean and 1% land. This land which lies mostly below the one meter mark above mean sea level, is entirely dependent on the stability of its surrounding marine environment.

However, the government of Maldives’ development approach undermines the stability of the balance of nature in the country. It entertains a policy of domestic aviation and airport infrastructure that is grossly and disproportionately overblown in the context, capacity and need, at the expense of multiple ecosystems. The policy to have a domestic airport at every 20-30 minute travel distance attempts to justify expansion that is financially and environmentally debilitating to the country.

The multitude of questionable and destructive ecocide projects like Faresmaathodaa Airport are not environmentally accounted. The extreme loss and damage inflicted on ecosystems, the loss of services they provide to communities and existing businesses dependent on them are not valued, as a matter of practice. These projects are conducted as if these natural systems have no inherent value as the natural defences of the country. It is a well established fact that the country’s reef ecosystem foundations were instrumental in defending these small, low-lying islands in the middle of the Indian ocean. The 2004 Asian Tsunami travelling at a speed of 500 mph was slowed down by these reef defences that took the brunt of the hit. To destroy and bury these defences willfully during a self-proclaimed ‘climate emergency’ is akin to digging its own grave. The government of Maldives is invested in free riding on the narrative that it faces an existential crisis due to global climate heating, and take no responsibility to cease widespread and irresponsible ecocide nationally.

Faresmaathodaa Airport Ecocide

The political fanfare and fireworks surrounding the Faresmaathodaa ecocide is a superficial show covering up extreme environmental loss and damage, the value of which is entirely dismissed and ignored. The airport was built by destroying 5 uninhabited islets south of the inhabited island of Faresmaathodaa. The reclamation component of the project is nearly MVR 80 million (~USD 5.3 million). According to the State broadcaster PSM, the airport project cost an estimated USD 10 million.

The environmental damage and destruction the project will cause is outlined in the project environmental assessment (EIA) of July 2018. The project was estimated to remove 14,000 to 16,000 trees from the impact area, although the environmental or social cost was not accounted. The EIA further said that

“coastal construction activities will involve significant adverse impacts on the marine water quality and marine life. The most significant will be the turbidity impacts from the dredging, reclamation and shore protection activities. Biota associated with the seabed within these footprints will be lost, either due to physical removal during dredging or burial during reclamation works.” (project EIA, pg.xvii – italics added).

The report further described the project’s proposed and anticipated future impacts, saying that,

“There are potentially severe impacts predicted due to hydrodynamic changes. The reclamation across five islands and funneling effect created between Faresmaathodaa and the airport may cause severe erosion on the eastern shoreline of Fares and western shoreline of Kan’dehdhudhuvaa. There is also strong likelihood of flooding on the airport due to the elevation and shore protection designs proposed, and given the fact that Faremaathodaa [sic] has a known history of coastal flooding.” (project EIA, pg.xvii – italics added).

The decision to ignore the environmental and ecological consequences of ecocide to build short-term, ecologically high-impact and loss-making infrastructure for political gain undermines every legal and governance requirement to develop Maldives sustainably. This approach to infrastructure development imposes a crippling environmental and financial burden on the country, incurring loss upon loss.

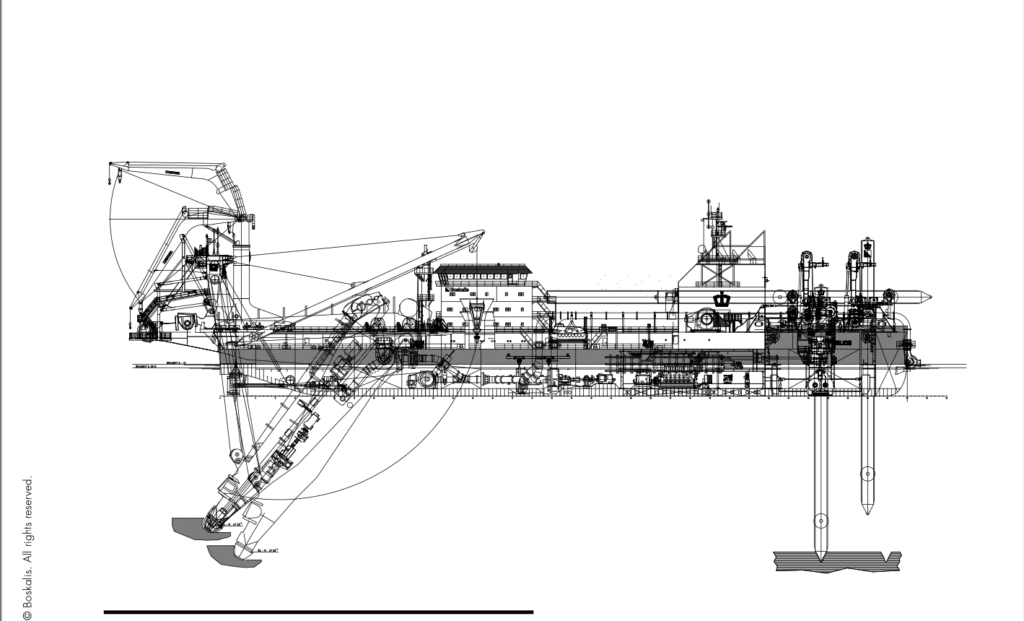

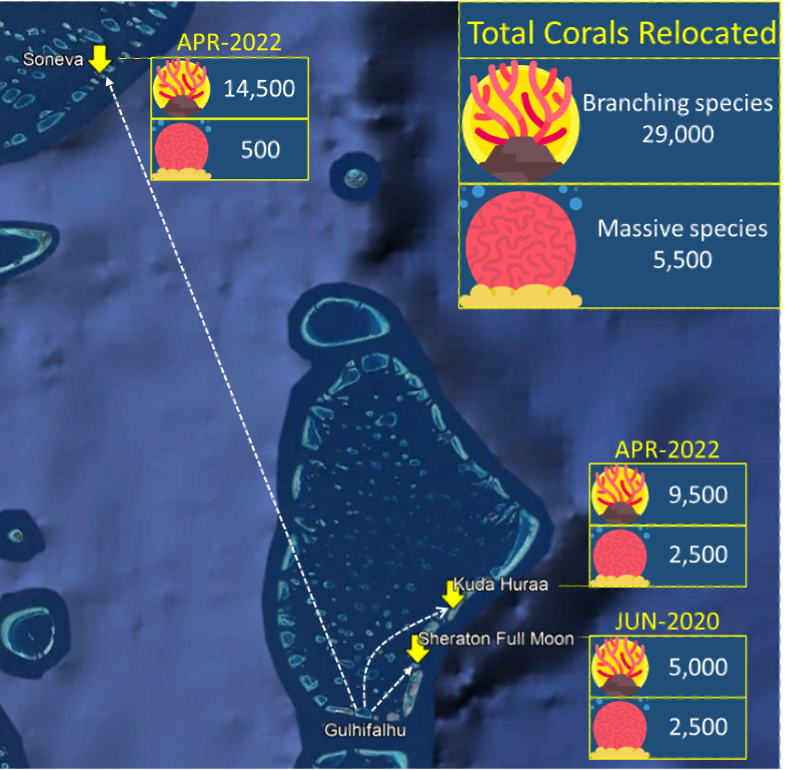

Kulhudhuffushi Airport Ecocide

Politically driven ecocide projects continue to plague the Maldivian people and their aspirations for meaningful change to improve their lives through sustainable development activities. Sustainability, viability, economic and financial feasibility are of little to no concern for politician-driven ecocide projects. In October 2017, the government of Maldives went ahead with the destruction of Kulhudhuffushi mangroves and wetland to build an airport in the middle of one of the largest wetland ecosystems in the country, amid public protests. State owned company MTCC Plc with no experience in airport development was assigned the project, using its first ever dredging vessel built by Netherlands company ICH Holland in China. In a press statement, the President’s Office said that the vessel, named “Mahaa Jarraafu is capable of conducting land reclamation activities without causing damage to the environment.” (italics added)

The project’s immediate negative consequences were widespread, including the displacement and dispossession of local livelihood resources and economies affecting over 400 families. Other impacts to the community showed when Kulhudhuffushi began to experience increased flooding which had significant direct impacts on people’s homes and property. Efforts by the #SaveMaldives Campaign and concerned stakeholders to protect the remaining part of the wetlands have been ignored by the current government.

In 2023, Kulhudhuffushi airport requires extensive shore-protection works as erosion threatens it. The national budget has thus far allocated over MVR 20 million (~USD 1.4 million) to address the continuing impacts of the destruction caused by the airport project. Today, nearly 6 years after the project began, Kulhudhuffushi Airport is still not fully operational. Notably, President Yameen Abdul Gayoom was impatient to inaugurate the airport project, and did so before the airport terminal could be completed, as part of his failed re-election campaign in 2018. The airport continues to suffer from significant critical infrastructure deficits which limit flight movements. Its operational functions were initially hindered by the absence of key operational components such as fire and rescue and ground handling services. To date, the airport has yet to install runway lights.

Hoarafushi Airport Ecocide

The ecocide case of Haa Alif Atoll Hoarafushi Airport which was a political project initiated in 2019 showed yet again the catastrophic consequences of willful ecosystem destruction by the government of Maldives and its political decision-makers. The airport was constructed in record time by the Maldives State owned company MTCC Plc (once again), and opened with the usual fanfare by President Solih in November 2019. Initial reports suggested the airport construction cost MVR 198 million (~USD 13.2 million) while another said it cost MVR 211 million (~USD 14 million). The government project portal shows that between 2019 and 2021, over MVR 233 million (~USD 15.5 million) had been spent on this project.

The project EIA’s First Addendum of March 2019, on the strength of which the project was approved, reached the following conclusion :

“The study found that through the implementation of the proposed practical and cost effective mitigation measures in this addendum report in conjunction with the EIA all significant impacts can be brought to an acceptable level.” (pg. 158)

This pivotal project EIA document provides no valuation or accounting for environmental or ecological loss and damage the project would cause. At this point, it might interest the reader to know that the producer of the Hoarafushi Airport EIA is the incumbent People’s Majlis (Maldives parliament) MP for Hoarafushi, Ahmed Saleem who ran for his parliamentary seat for this constituency in April 2019, with a pledge to develop this airport. MP Saleem is also the Chairperson of the permanent parliamentary committee known as the Environment and Climate Change Committee. In this capacity, he is also known for having submitted an application in December 2019 to the International Criminal Court on behalf of the Maldives, to make ecocide an international crime. The situation could hardly be more ironic, duplicitous or dishonorable.

Just five months after its November 2019 inauguration, Hoarafushi Airport was inundated due to high winds and tidal surges during the monsoon in May 2020, causing significant losses raising key questions about the project’s planning, construction and management. In April 2021, reports emerged that the causeway linking Hoarafushi island to the airport would be removed, confirming the serious gaps in the project’s planning, approval and implementation. A scientific study on coastal flooding in the Maldives published in 2021 observed that Hoarafushi island experiences the “highest incoming waves in the archipelago”. The fact that the Hoarafushi Airport EIA addendum was produced by a technical practitioner who either missed or deliberately ignored this basic scientific fact is astounding. This leaves room to suggest that the evident personal conflict of interest in this case trumped the public interest. The fact that the Maldives Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also failed to act on this fundamental fact by approving the airport EIA is indicative of monumental regulatory failures. These failures highlight the political realities that make unchecked ecocide actively endorsed and normative in the Maldives. The complete absence of accountability and professional due diligence undermines the ecological and human security, and therefore, the present and future stability of the country.

Ecocide as Achievement for Political Expedience

This brings me back to the case of Faresmaathodaa Airport. It is not lost to the Maldivian people that Faresmaathodaa is the home island of the incumbent Minister for National Planning, Housing and Infrastructure, Mohamed Aslam. Similar to Mr Saleem MP for Hoarafushi, he also has a professional history of producing EIAs. Prior to his current cabinet post, Mr Aslam, who holds a BSc in Geological Oceanography, held the position of director at the EIA consultancy company La Mer. There, he was personally involved in the production of the EIA to construct a causeway between the islands of Madaveli and Hoadedhdhoo in Gaaf Dhaal atoll, in 2016. This project was also commissioned to MTCC Plc, and have proved to be an ongoing, financially wasteful and catastrophic ecocide project since 2012. This history has relevance to the kind of decision-making we see by these politicians.

The Faresmaathodaa Airport project plans pre-date the current administration. The opportunity to prevent the loss of environmental stability of 6 islands and their surrounding natural defences and assets was available to this government. President Solih’s government and his cabinet in which Mr Aslam sits, chose not to do that. They chose to commit willful ecocide in this case, as in several others, continuing to gaslight the public and attempt to package these acts of destruction and irreversible losses as achievements.

As long as political decision-makers in influential positions are allowed to exploit public finances and environmental assets for personal political expedience, the Maldives vulnerability to climate disasters will continue to spiral. High level officials including the President, members of his Cabinet and their partners in the Peoples’ Majlis continue to celebrate ecocide as achievement in the Maldives. This stands in absolute and stark contrast to the narrative of vulnerability to climate change these same public officials attempt to sell, especially internationally. Their gross professional misconduct and failure to uphold legal and public duty should be understood as that.

This article, with its accompanying images, was first published on 19 March 2023 on SaveMaldives.net Click here to visit the original article and sign the petition #SaveAddu Biosphere Reserve. Re-posted here with author’s permission.

Image 1: Kulhudhuffushi before the Airport Ecocide 📷 Save Maldives campaign, Image 2: Faresmaathodaa (2011 – 2022) 📷 Google Earth, Image 3: Kulhudhuffushi (2006 – 2022) 📷 Google Earth, Image 4: Hoarafushi (2016 – 2022) 📷 Google Earth