Let them eat Basmati

by Azra Naseem

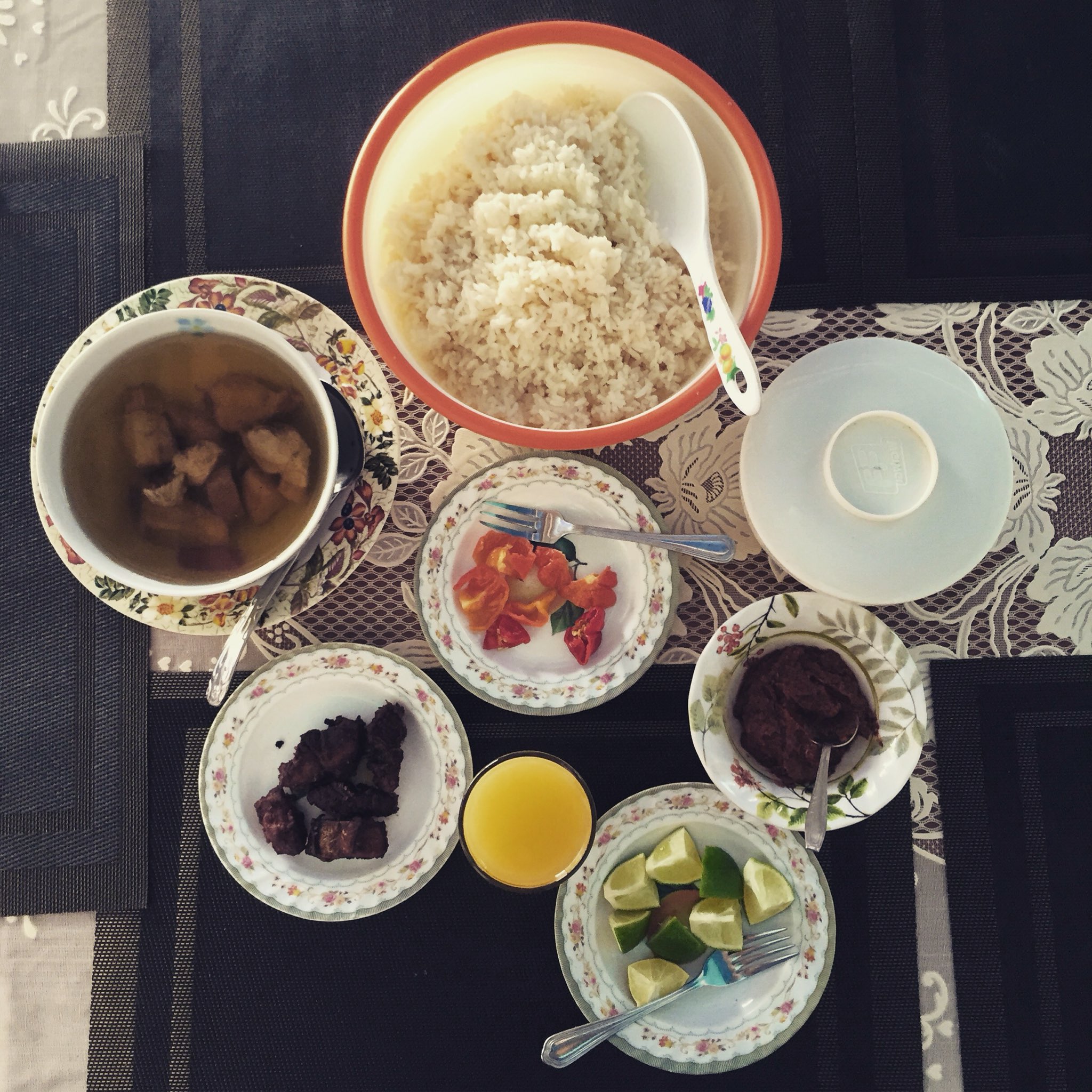

The price of rice, sugar and flour went up by 100 percent in the Maldives this month. Rice, sugar and flour—‘han’doo, hakuru, fuh’ always said together, always in that order, and collectively known as kaadu—are essential ingredients of the Maldivian diet. Without han’doo there would be no lunch and no dinner; and without fuh there would be no roshi, no hedhikaa, and without hakuru, tea is not really sai.

Any difficulties in getting Han’doo-hakuru-fuh triggers existential crises, and, raises the spectre of famine. The oldest generation alive today begins reliving memories of when the knock-on effect of the Second World War led to a shortage of kaadu in the Maldives and people had to eat magoo faiy, leaves of the Magoo plant (beach lettuce, or Scaevola taccada), that grow abundant in salty island soil. It is no surprise then that talk turned to magoo faiy recipes as soon as the government made its shock announcement it was cutting off state subsidies that made kaadu affordable for most people.

Broadly speaking, no leader has dared touch the price of kaadu since Amin Didi who was president when people had to eat magoo faiy.

He was lynched.

Probably with this in mind, a system was put in place that allows government control over kaadu prices—the State Trading Organisation (STO) imports and sells the products cheaper than they would be if left to the invisible hand of the market. To make this possible, STO gets land in Male’—and on all other islands it has a presence on—at dirt cheap rates, and enjoys a range of advantages and privileges not available to private companies. The system worked, and no leader dared upset the rice cart.

Until President Yameen, the Gatu Raees— or the President with Balls.

President Balls never really interacts with the people directly, especially when there is difficult news to be shared. He dispatches a group of hand-picked loyalists to carry out the task whose brief appears to be ‘Defend my decision no matter what. I don’t care how.’ Justifying the kaadu price hike fell to Chair of the National Economic Council and Minister at the President’s Office, Ahmed Zuhoor. Unlike the President, I am no economist—that is, I don’t have an unapplied dusty old MBA dating back thirty years or a reputation for money laundering or running a blackmarket economy—but even I knew some of these justifications make no sense.

First Zuhoor said the subsidies had to be cut because migrant workers are using them, not just real people. There are over 150,000 migrant workers in the Maldives, and another 10,000 or so undocumented ones, he said. The government intends to expand the tourism industry to cater to seven million tourists a year—more than double the numbers today— which means more migrant workers. “They will be buying the subsidised kaadu too.” These (un)people, coming over here, taking our jobs, and eating our subsidised kaadu. We cannot afford that. We will certainly not tolerate that.

Also, resorts are buying the same subsidised kaadu, charging US$2000 a night for a water bungalow with an attendant Maldivian butler who serves sashimi with government-subsidised long-grain rice. Another reason to cut subsidies for everyone.

Besides, Maldivians—at least everyone in Minister Zuhoor’s circle—live such a plush life under Yameen’s successful economic policies we won’t eat long-grain rice even if our lives depended on it. Nah, it’s Basmati or nothing, baby. (Long-grain rice is subsidised, Basmati is not.)

What’s more, said Zuhoor, people dine out a lot. “Poor people eat at home, in the kitchen. They don’t go out to eat.” Ergo, if you go to a coffeeshop or any number of tea houses, hotaa, or street stalls, to get your hedhikaa, your coffee and your roshi, you are an affluent, spoilt, middle-class hipster who really should know better than to be a drain on the economy by putting subsidised sugar in your Flat White.

Outside the charmed circle of Zuhoor’s friends and family, a substantial percentage of the people who eat from the hotaas —at least in Male’—are people who don’t have a kitchen to cook in. Most of Male’s residents today do not own property on the island, they rent small spaces at extortionate prices. Dozens of people crammed into small flats, sleeping in shifts because there aren’t enough beds—or floor space—for everyone to sleep at night; where there is barely room to breathe, let alone cook. Hundreds of people who are in Male’ for trade trips from the islands, who sleep on their boats and have no choice but to eat from the hotaas. Thousands of male residents who, even if they had access to a kitchen, do not know what to do in one without their mothers, daughters, sisters or wives. And thousands of migrant workers who are treated as subhumans, who live in abject squalor and are only allowed in Maldivian kitchens to cook and clean for their Masters, and who are the only people in the country on whose income the government has levied a tax. These are the people who make up the majority of what Zuhoor describes as ‘the rich people who eat out’ that really don’t need subsidies.

The other justification was that Maldives itself is now too rich to qualify for aid from the international community. “We are no longer counted among the Least Developed Countries”, said Zuhoor. He did not mention this fact dates back to 2011. Problem is, he said, international financial organisations are not giving loans to the Maldives if we don’t cut our expenses. The IMF and World Bank strategies with their Structural Adjustments Programmes (SAPs) that sap the life out of debt-ridden economies in developing countries are not a secret anymore—these are facts readily accessible to the interested. When in debt, especially when in as much debt as the Maldives is in today (over 65 per cent of the GDP last year and counting), there is little else to do but agree to the demands of the higher powers, tighten belts, and pay up. Just look at Greece.

Question is, why were the kaadu subsidies the first thing to go?

Zuhoor said the government can save over MVR100 million by cutting the subsidies. In the grand scheme of things, what is MVR100 million in a country which is spending close to a billion US dollars, at least, on ‘development projects’ all over the country? Dozens of roads are being ‘developed’ with tar on small islands with almost no traffic—highways on islands barely a kilometre long; council flats on sparsely populated islands where land shortage is not even a distant thought in a worrier’s head; and airports on islands within walking distance of each other. Is any of this necessary for the survival of the people? No. Survival of the government, maybe – if you accept the warped strategy that such environmentally and financially costly excesses is ‘development’.

And this is before we begin to take in the mind-boggling waste in and around the so-called Greater Male’ Area.

I’ve talked so much about the Male’-Hulhule’ bridge, I won’t go there again. Enough to say it costs over US$200 million; it takes five minutes by speedboat to travel to Hulhule’. But, there’s still a lot to be said on the mini-projects that have sprung up around The Bridge.

For instance, how much does it cost—keeping in mind electricity prices, too, have been pushed higher—to light up in red unblinking red—‘CHINA-MALDIVES FRIENDSHIP FOREVER’—on a barge in the middle of the sea night after night? As if this is not enough, the government is now paying MVR8 million to build a platform to view construction work on the bridge. Over six percent of the money saved by cutting subsidies spent on providing people a place to sit and watch Chinese labourers doing construction work on a bridge, while sipping their coffee sweetened with non-subsidised sugar, munching on non-subsidised mas-roshi in the afternoon, and Basmati under the moon. Oh, to be a rich Yameenite in today’s Maldives. If this is not super cool ‘development’ worth sacrificing affordable kaadu for everyone, what is?

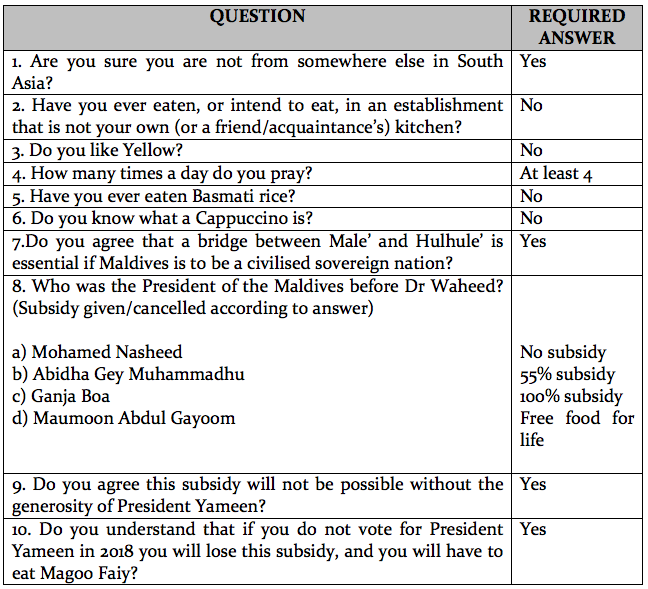

I share the suspicion of many that the subsidies had to go first so they can make a grand comeback. In their next incarnation they will return as a powerful symbol of President Yameen’s Largesse. To announce the taking away of something, and to return it re-packaged as The President’s Generosity, is now a familiar strategy. So it is likely to be with the kaadu subsidies.

This re-branding is already in the making. In fact, it had already begun when the subsidy cut was first announced: “exceptions will be made for The Needy”, Zuhoor said. Although it was not known at the time how one qualified as a member of The Needy Caste, details are emerging, based on questions asked, and answer required, when people apply for kaadu subsidy. Here’s a sample (sub-text).

Genuflect, people. Say altogether: Thank you, #HEPY. Long Live Dear Leader.

Photo: Lucas Jalyl

Although the Maldives’ luxury tourism industry is ostensibly segregated from the country’s politics, their connections run deep. In 2008, the Maldives began the project of democratisation with a new Constitution following street protests calling for democratic reform in September 2003 and August 2005. A modern tax regime was introduced, and tourism on inhabited islands was decriminalised to alleviate the widening socio-economic gap.

Although the Maldives’ luxury tourism industry is ostensibly segregated from the country’s politics, their connections run deep. In 2008, the Maldives began the project of democratisation with a new Constitution following street protests calling for democratic reform in September 2003 and August 2005. A modern tax regime was introduced, and tourism on inhabited islands was decriminalised to alleviate the widening socio-economic gap. President Yameen described the secessionist movement in the south of the Maldives as the “biggest threat to national unity”, although British imperial ambitions in the Maldives were limited to its strategic location due to a lack of natural resources. Infighting among Maldivian royal families and domination of trade by Borah traders with the help of Imperial Britain paved the way for the Maldives to become a protected state.

President Yameen described the secessionist movement in the south of the Maldives as the “biggest threat to national unity”, although British imperial ambitions in the Maldives were limited to its strategic location due to a lack of natural resources. Infighting among Maldivian royal families and domination of trade by Borah traders with the help of Imperial Britain paved the way for the Maldives to become a protected state.