Why should CMAG keep Maldives on its agenda?

by Azra Naseem

Questions over the government’s legitimacy, continuing allegations of human rights abuses by security forces and unanswered questions over the transfer of power on 7 February are just some of the reasons why the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG) should keep the Maldives under scrutiny.

On 28 October 2011, the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG) agreed that it had been ‘too reactive, and not sufficiently proactive’ in fulfilling its purpose: dealing with serious or persistent violations of the Commonwealth values and principles.

It decided, therefore, to broaden its mandate, and specified the following types of situations as constituting serious or persistent violations of Commonwealth values:

1. The unilateral abrogation of a democratic constitution or serious threats to constitutional rule;

2. The suspension or prevention of the lawful functioning of parliament or other key democratic institutions;

3. The postponement of national elections without constitutional or other reasonable justification;

4. The systematic denial of political space, such as through detention of political leaders or restriction of freedom of association, assembly or expression.

CMAG placed the Maldives under scrutiny following the end of the first democratically elected Maldivian government on 7 February under questionable circumstances. A Commission of National Inquiry set-up by the caretaker government of Dr Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik has found there was nothing unconstitutional about the transfer of power.

There are serious issues with this finding; and many holes in the current government’s core argument for removing the Maldives from the CMAG agenda: ‘all is well’ with the Maldivian democracy and, therefore, keeping Maldives under scrutiny is not just beyond the institution’s mandate but is also a violation of the country’s sovereignty.

The flaws in this argument, and the disinformation on which it is based, become evident when the situation in the Maldives is examined in light of each of the four main tasks in the CMAG mandate mentioned above.

This is a worthwhile task to undertake today, as CMAG meets in New York to make a decision on the Maldives.

1. The unilateral abrogation of a democratic constitution or serious threats to Constitutional rule.

Dr Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik was sworn in as the President of the Maldives under Article 126 of the Constitution, as a person temporarily discharging the duties of a President. The Constitution does not specify how long ‘temporary’ can be. Thus, the current government has conveniently interpreted it as meaning until the end of an ongoing presidential term, however long that maybe.

Be that as it may, the claim that the Constitution forbids an early election, or the often-repeated claim that a Constitutional amendment is required if presidential elections are to be held before the natural end of a presidential term, is not correct.

The Constitution does foresee circumstances where an election may have to be held during an ongoing presidential term:

Article 125 (c)

Where fresh presidential elections have to be held for any reason during the currency of an ongoing presidential term…

There is no need for the Constitution to be amended to hold a presidential election ahead of the one scheduled for 2013.

This is why the Commonwealth, the European Union and the United Kingdom, Canada—and a few international actors who have dared insist on early elections—are not calling for the government to act against the country’s Constitution, as Waheed so audaciously claimed at the recent United Nations General Assembly:

We were asked to bring to an end a Presidential term and hold elections even if they were not allowed under the Constitution. We were asked in no uncertain terms to abide by such instructions even if it meant amending the Constitution.

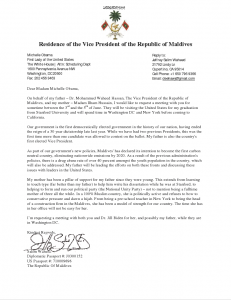

It is one thing to Twitter-brag about a meeting with President Obama that never happened:

Met President Obama tonight. He sends his best wishes to the people of Maldives.

— Mohamed Waheed (@DrWaheedH) September 25, 2012

or even to unbecomingly grovel for one:

it is quite another matter, however, to attempt to deceive the international community about what the country’s Constitution says, and what his government has been doing since coming to power. Unlike the mere embarrassment caused by Waheed’s sycophancy, this is behavior that poses the kind of serious threat to constitutional rule that falls well within the mandate of CMAG.

Accept, for the sake of argument, that the transfer of power was legitimate. Also, accept the Coalition Government’s reading of the Constitution that a caretaker president can remain as leader of the country until the end of an ongoing presidential term.

Is Waheed’s presidency then constitutional?

Only if he, as the caretaker president, faithfully runs the elected government and its policies until the people can elect their next government. Indeed, Waheed is fully aware that this is the case and attempted, until recently, to present his government as carrying out this responsibility:

My government is a continuation of the previous government under then president Nasheed and hence there should be no doubt on this score.

That’s what Waheed told Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh during a visit to India in May 2012.

This, again, is simply not true. What Waheed has done, instead, is change the elected MDP government beyond all recognition.

First it sacked Nasheed’s entire cabinet, and replaced it mostly with hardline supporters of the authoritarian regime the Maldivian people voted out of office in 2008. Within a month, he had also appointed 11 new deputy ministers, and a whole slew of State Ministers.

At the time—with 15 new State and Deputy Ministers in place—Waheed’s spokesperson, Abbas Adil Riza, told the media there would be no more such appointments. In April, the government upped the figure to number that ‘would not exceed 80‘. The appointments continue to this day, with a fourth advisor to the President appointed only this week.

Waheed also dramatically changed the institutional structure of the government, establishing a new Ministry of Gender Family and Human Rights and a Ministry of Environment, as well as new state companies, while handing out lucrative board memberships of such companies to his relatives and friends.

This was followed by policy changes that either amended, completely reversed, or turned on its head major policies of the MDP government from healthcare; housing; education; fishing; finance; tourism promotion and revenue structures; taxation and import duties; civil service wage structure and foreign investment to energy and foreign policy. Radical new changes are also now being proposed to how and where people should live.

The current government is not the MDP government that people elected. Waheed, as caretaker president—and who has told the international community that ‘there should be no doubt’ that he is continuing Nasheed’s government—has replaced it with a government of his own, one that was not voted for by the people.

How is this democratic? And how is it constitutional?

2. The suspension or prevention of the lawful functioning of parliament or other key democratic institutions

While questions remain over the legitimacy of the executive branch of the three separated powers, the Maldivian Parliament remains indefinitely suspended since the end of July, and judicial independence has been seriously compromised.

The CMAG has, among other things, surely considered the following evidence:

Maldives: securing an independent judiciary in a time of transition, International Commission of Jurists, February 2011

A legacy of authoritarianism: a dossier on the Maldivian judiciary, Government of Maldives, February 2012

The Failed Silent Coup, Aishath Velezinee, August 2012

And it must, by now, be fully aware of the role of the Judicial Service Commission in the dismissal of Article 285 of the Constitution as ‘symbolic’, allowing criminals such as Abdulla Mohamed—at the centre of the events that led to the downfall of the country’s first democratically elected government on 7 February—to remain on the bench.

The current government has now been in power for close to eight months. Bar hyperbolic rhetoric about judicial reform, it has done nothing to restore judicial independence. In fact, the use of courts to pursue political ends has increased in the past months with various rulings from both higher and lower courts that clearly display political partisanship.

In the months since this government has come to power, the independence of key democratic institutions such as the Human Rights Commission, the Police Integrity Commission, the Elections Commission and the Anti-Corruption Commission have all been called into question, sometimes by members of the Commissions themselves.

If the Maldivian democracy is to be saved, CMAG must retain the Maldives on its agenda until such time as this government shows it is serious about judicial reform, and proves beyond doubt that it is not interfering with, or meddling in, the functioning of other key democratic institutions of the country.

Until then, it must not accept Waheed’s ridiculous rhetoric—based on lies and false premises—that pressure for such reform from international actors such as CMAG means ‘small justice […] being served for a small state.’

3. The postponement of national elections without constitutional or other reasonable justification

The government first attempted to delay elections by claiming that the electoral structure was too weak for such an event. When the Elections Commission countered, saying it was ready and well able for an election, the government took to spreading the misinformation that an election can only be held with a Constitutional amendment.

As discussed under point 1 above, presidential elections are being withheld from the Maldivian people by misinterpreting (to put it kindly) the Constitution. And, during this delay, the caretaker president is systematically and deliberately tearing down the elected government and replacing it with an unelected ‘Coalition Government’ of his own.

Where then is the government of the people by the people for the people?

4. The systematic denial of political space, such as through detention of political leaders or restriction of freedom of association, assembly or expression.

With the assumption of power, Waheed’s government, together with the police and military personnel whose mutiny made the events of 7 February possible, has systematically and brutally shut down all avenues for legitimate protest and assembly.

The police brutality of 8 February is well documented, and is one of the few crimes against the Maldivian people to which this government has admitted. Yet, despite continuation of such police brutality for months, to date, there has been no action taken against those who carried out these atrocities.

Having used the law and brute force to evict MDP supporters from any public space they occupied for demonstrations, the government then used the corrupted judiciary to restrict freedom of movement of almost all key MDP activists, party supporters, and reformists.

According to Impunity Watch Maldives, published by the MDP this month, there have been 130 documented cases of police brutality against protesters since Waheed began his job as caretaker president. Over 800 protesters have been detained by police for participating in protests calling for early elections, and 80 have been charged with ‘terrorism’.

17 MDP Parliament Members and 19 party officials have been beaten or arrested by police; and seven MPs and 29 party officials have been summoned for questioning and/or are facing prosecution. These targeted arrests have also included three Ministers of Nasheed’s government—the government that Waheed claims to be faithfully continuing.

The International Federation of Human Rights has documented much of these abuses in its report, ‘From sunrise to sunset: Maldives backtracking on democracy‘ published this month, as has the Amnesty International in its report, ‘The other side of paradise: a human rights crisis in the Maldives‘.

And yet, no police officer has been prosecuted to date, nor has there been any condemnation by the government of any of the violence and human rights abuses. Neither has the Human Rights Commission of the Maldives (HRCM) instigated any investigations into this well documented police brutality and denial of civil and political freedoms fundamental to the proper functioning of democracy. This failure of the HRCM and the Maldivian government shows clearly the Maldivian people’s need of the international community to deliver them their rights.

Media freedom, too, has been severely restricted for outlets sympathetic to the ousted MDP government. Raajje TV, for example, was told that it would not receive police cooperation during coverage of protests, its journalists were targeted for violence, and was banned from covering some key events. MDP has also documented 11 instances where police have beaten and/or arrested journalists who covered the protests and recorded police brutality on the streets of Male’. Both Reporters Without Borders and the Committee to Protect Journalists (international actors again), have documented these issues and expressed their concern.

The caretaker government of Waheed has taken no action. Nor has there been any investigation whatsoever into the violent takeover of the State broadcaster MNBC One on 7 February, and the arbitrary reversal of the Station’s name and logo to TVM—what it used to be when it was a propaganda machine for the dictatorship.

Nothing demonstrates more clearly and succinctly, however, the extent to which freedom of expression has been limited in the Maldives today than the fate of the Dhivehi word Baaghee—traitor. The word can no longer be used in the Maldivian public sphere without fear of harsh reprisals from the police or being caught by the long (and crooked) arm of the law. It is a word effectively banned from the Maldivian vocabulary.

Defamation proceedings are, in fact, due to start in a few days against former President Nasheed for using the word in relation to Mohamed Nazim and Abdulla Riyaz, the current government’s Defence Minister and Police Commissioner respectively. The former president is also to be prosecuted for his role in the arrest of Abdulla Mohamed, the criminal judge, while all complaints of judicial misconduct against him remain unexamined and ignored.

Perhaps President Waheed’s ardent admiration of President Obama, at a guess, is about the latter’s looks; for it is most certainly not about his espoused beliefs. This is what Obama had to say at the same forum where Waheed supposedly met him:

Moreover, as President of our country, and Commander-in-Chief of our military, I accept that people are going to call me awful things every day, and I will always defend their right to do so.

President Waheed and key officials of his government, in contrast, jail people for the same.

If CMAG disregards the evidence before it, and removes the Maldives from its agenda, it would not only give blessing to a government that came to power through seriously questionable means—with the help of a police/military mutiny among other things—; it would also close the door on any opportunities that remain for Maldivians to reclaim, through peaceful and democratic means, their right to govern themselves .

Obama’s eloquent words:

[E]ven as there will be huge challenges that come with a transition to democracy, I am convinced that ultimately government of the people, by the people and for the people is more likely to bring about the stability, prosperity, and individual opportunity that serve as a basis for peace in our world.

appear hollow in light of how his government has chosen to favour the ‘stability’ of Waheed’s government over the inevitably chaotic fight for the Maldivian people’s right to an elected government.

As disappointing and damaging to the Maldivian democracy as the US stance has been, given the State’s realist foreign policy and history of supporting the ‘stability’ provided by dictators, it is a stance that should not surprise anyone.

However, if the Commonwealth, too, puts ‘stability’ before the right of people to govern themselves, and decides that the Maldives should be removed from CMAG’s agenda—despite all the violations of its Constitution, rule of law, and human rights of the people—it would be a different matter altogether.

It would not simply be a betrayal of the Maldivian people, but also of all that the Commonwealth stands for, and of the very concept of democracy itself.