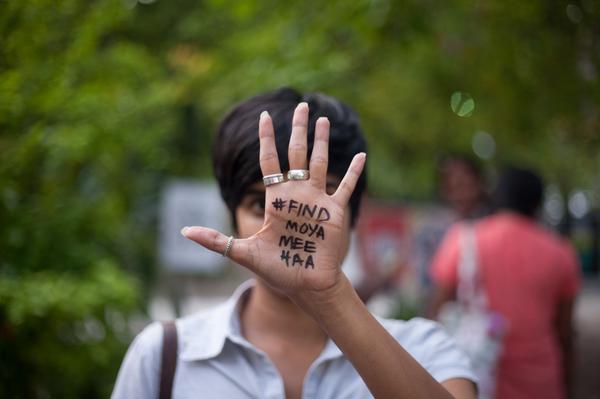

#FindMoyameehaa

I’m wondering just how much

To you I really said

Concerning all the boys that come

Down a road like me

Are they enemies or victims

Of your society?—-‘Ballad of Donald White’, Bob Dylan, From the last post on Rizwan’s Blog

Yesterday night, two weeks ago, was the last time anyone saw Ahmed Rizwan Abdulla, 28-year-old journalist, blogger, human rights advocate and all-round great person.

A lot—yet nothing—has happened since Rizwan was reported missing to the Maldives Police Service (MPS) on 13 August.

On 15 August Rizwan’s family and friends organised a search of Hulhumale’, the island neighbouring Male’ on which Rizwan lives on his own. Starting with the desolate, deserted areas—-of which there are many—-the search party combed the whole island. It was in vain.

On 16 August Rizwan’s friends and colleagues, who obtained CCTV footage from the Male’-Hulhumale’ ferry terminal from the night he was last seen, identified him on camera buying a ticket and going into the waiting area to board the 1:00 a.m. ferry on 8 August. This footage has since been made public. For the next twenty minutes or so—-the amount of time it takes for the ferry to reach Hulhumale’—-Rizwan was on Twitter. Between 1:02 a.m. he sent out 11 (mostly re-) Tweets, beginning with this one, which said he had just boarded the ferry:

ferry for gaza.. w/ mollywood superstar eueuope.

— مجنون (@moyameehaa) August 7, 2014

His last Tweet was at 1:17 a.m three minutes before the ferry would have reached Hulhumale’. According to Rizwan’s employer, Minivan News, he sent a Viber message at 1:42 a.m. The newspaper further reports that according to Rizwan’s telephone service provider that his mobile phone was last used at 2:36 a.m. at a location in Male’. Since then, nothing.

There was a shocking development to the story a few days after the search for Rizwan began. On the night he was last seen, two witnesses saw a man being abducted from outside Rizwan’s apartment around 2:00 a.m. Minivan News, which withheld the information until it was made public by other news outlets, published details of the abduction on 18 August. The witnesses heard screaming and saw the captive, held at knife point by a tall thin man, being bundled into a red car which drove away at speed. The witnesses contacted the police immediately. They also recovered a knife from the scene. The police took a statement and confiscated the knife.

And that was that.

It is mind-boggling that there were no searches in Hulhumale’ after eye-witness reports of an abduction, no sealing off of exits to and from the island, no investigation in and around the area of the abduction to at least ascertain who had been bundled into the car. If the police had done any of this, Rizwan’s family would have been aware of his disappearance so much sooner. Two weeks on, the police still don’t seem to have managed to locate the red car—-this on a 700 hectare island with the total number of cars totalling around fifty, if that.

Outrage at police ‘incompetence’ has grown steadily as days turn into weeks without news of Rizwan’s whereabouts. MPS’ reaction to the criticism has been petulant, like an offended prima donna. It issued a long statement demanding that the public stop criticising police given how brilliant they obviously are; and, unbelievably, proceeded to hold a press conference about Rizwan to which all media outlets bar his own Minivan News was invited.

Speculation that MPS does not want Rizwan found is becoming fact as time passes with no leads. How incompetent does a force have to be to remain clueless about how a person was abducted from a small island? How many red cars can be hidden on such a small piece of land, surrounded by the sea? How difficult would it be to locate the individuals caught on CCTV following Rizwan at the ferry terminal in Male’? It is common knowledge that life in Male’ is now governed by an ‘unholy alliance’ of ‘born-again’ fanatically ‘religious’ gangsters and thugs controlled by politicians and fundamentalists.

Whatever the police is driven by—fear, complicity, support—it is certain the government shares its ‘could not care less’ attitude. President Yameen’s callous response on 20 August to news of Rizwan’s disappearance confirmed this: ‘I cannot comment on anything and everything that happens, can I? The police are probably looking into it.’

It is as if the disappearance of a young man, a journalist and well-known human rights advocate—the first incident of its kind in the Maldives—is as routine as a mislaid shopping list. The President, who campaigned as Saviour of the youth population, had not a word to say about the abduction and disappearance a young man of vast potential. Yameen chose, instead, to wax lyrical on his success at begging in China, having procured a 100 million US dollars in aid money for building a bridge between Male’ and Hulhumale’, the island where Rizwan is feared to have been abducted from.

Who wants a bridge to an island that is so unsafe? An island where women are raped in broad daylight and young men disappear without a trace? Where gangsters and violent extremists rule, where the police turn a blind eye to crime and where the streets have no lights?

It is quite extraordinary that a President of a country sees no need to express concern for a citizen whose sudden disappearance has led to statements from international bodies ranging from the UN Human Rights Commissioner to media associations such as Reporters Without Borders, CPJ, IFJ and South Asia Media Solidarity Network as well as news outlets and human rights advocates in the region and across the world. In some of today’s news coverage, Rizwan’s name is on top of the world’s missing journalists’ list. According to Minivan News, many foreign diplomats based in Colombo have made the time to listen to its concerns about Rizwan’s abduction.

Diplomats from Oz, Ger, Neth, Fra, Can, Switz & EU found time to meet with @minivannews today as Home Min failed to invite us to Riz presser

— Daniel Bosley (@dbosley80) August 20, 2014

Perhaps prompted by diplomatic concern, over a week after Rizwan’s disappearance became public knowledge, the Maldives Foreign Ministry finally issued a hastily put together statement yesterday, full of factual and other types of mistakes, expressing a perfunctory concern hard to accept as sincere.

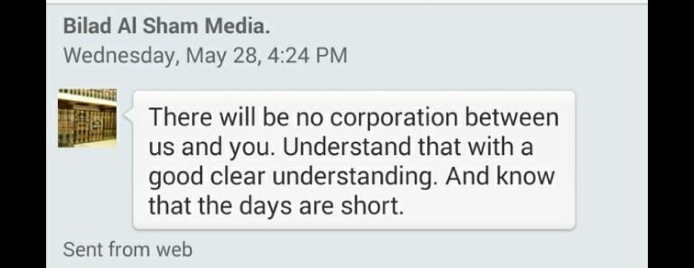

While the politicians, the gangsters and the religious fanatics with their support of Jihad, beheadings and other forms of killing trip over each other to ignore, laugh about, cover-up and prevent knowledge of what has happened to Rizwan, friends, family, and admirers of his deep humanity, are unflagging in their hopes and efforts to find him safe and sound.

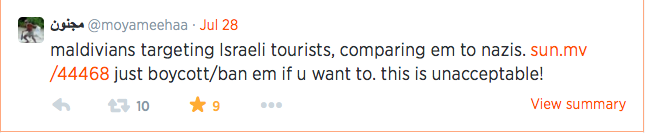

It is on social media, where he is known as Moyameeha, that Rizwan has made his widest impact. The Maldivian Twitter community is especially bereft without his presence. It is not surprising. The off-line Maldivian society has been largely taken over by gangs, zealots and bigots. There is no safe place for people like Rizwan—with bold ideas, open minds and creativity—to come together in real life. So they gather on Twitter—the most free of modern media platforms—exchange thoughts, discuss politics, make poetry and music, argue, joke, laugh, and cry, become friends and form the kind of free, liberal and tolerant public sphere they cannot have off-line. Rizwan is a shining star of that community, one of its well-liked and giving members. The community wants him back.

Close friends have set-up a website, findmoyameeha.com, where everything that is officially said and done in relation to Rizwan’s disappearance is gathered in one place. It also counts every passing second since he went missing. Friends have also set up Facebook pages dedicated to finding Rizwan while existing Facebook pages that support him have created a repository of online tributes:

Bloggers, who look up to him as one of the first to make an impact in the sphere, have been paying homage, re-finding and sharing some of his most moving posts. Rizwan’s friends discuss his poetry, his love of music (and obsession with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan), his enthusiasm for Dhivehi language, folklore and history, and most of all his never-ending good nature and empathy. Even the deeply divided and highly politicised journalistic community appears to be waking from a deep slumber, and putting their differences aside to demand that efforts to find Rizwan be stepped up.

Over the past few years the Maldives Police Service has become highly adept at being ‘incompetent’, at being ‘unable’ to solve the crimes they don’t want solved while putting all their efforts into hunting down bootleggers, cannabis smokers and petty criminals. If they catch any major offenders, the corrupt judiciary lets them go; so why bother? This being police ‘best practice’, a majority of the Maldivian population now choose to ‘forget’ unsolved crimes, stop asking questions, and carry on as nothing happened.

Not this time. Rizwan’s family, friends, supporters and like-minded journalists are not going to stop asking questions and looking for answers. Because if they do, it is the last nail in the coffin of Rizwan’s vision—shared by those looking for him—of a tolerant Maldivian society in which people are free to think, embrace diversity and difference, be creative, live safely and have the right to peace and happiness.

Ahmed Rizwan Abdulla, a Maldivian journalist, blogger and human rights advocate, is missing. The 28-year-old was last seen by his family on 7 August. Unlike most Maldivians of his age, Rizwan does not live with his family but rents an apartment in Hulhumale’, a 20-minute ferry ride from Male’ the capital. Rizwan is a deeply spiritual person, known to enjoy solitude. It is not unheard of for him to take time off from society to indulge in the right to be left alone. His close friends know that. This time, however, is different.

Ahmed Rizwan Abdulla, a Maldivian journalist, blogger and human rights advocate, is missing. The 28-year-old was last seen by his family on 7 August. Unlike most Maldivians of his age, Rizwan does not live with his family but rents an apartment in Hulhumale’, a 20-minute ferry ride from Male’ the capital. Rizwan is a deeply spiritual person, known to enjoy solitude. It is not unheard of for him to take time off from society to indulge in the right to be left alone. His close friends know that. This time, however, is different.