The long road from Islam to Islamism: a short history

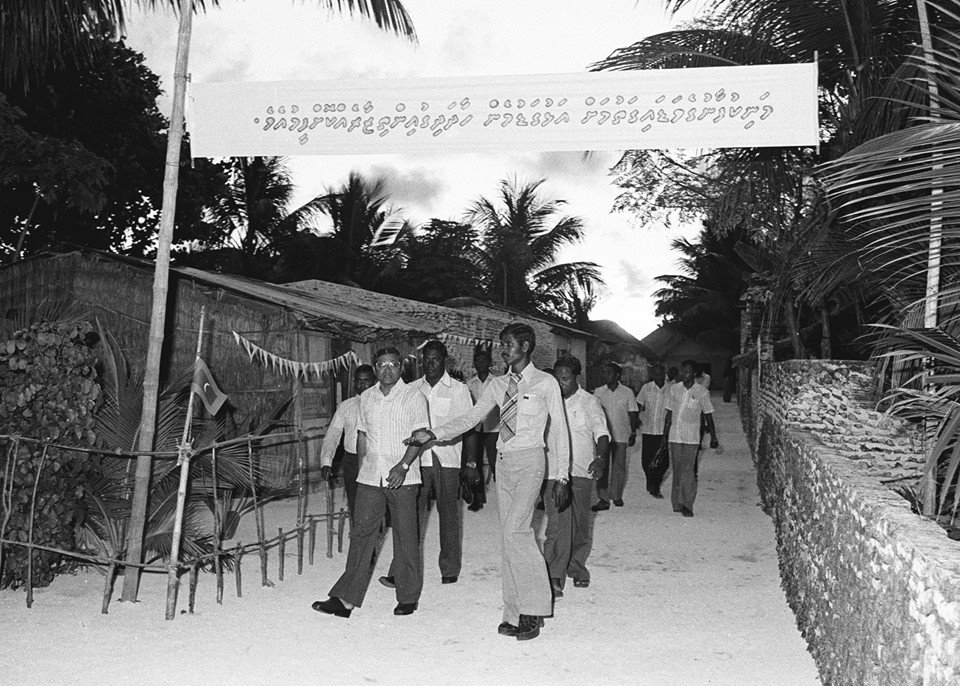

Gayoom, who ruled the Maldives for 30 years (1978-2008), was the country’s third president. Gayoom had spent most of his adolescent years in Egypt, having arrived there at the age of 12 in 1950 and left in 1969 as a graduate of Al-Azhar University. His politics, faith and worldview was largely shaped by what he saw and learned during almost two decades in the Middle East. When he was sworn in as president of the Maldives in November 1978, Iran was paralysed by demonstrations that heralded the Islamic Revolution. Relations between ‘the Arab world’ and the West were tense after the Arab-Israeli War of 1967 and the OPEC-led oil embargo in 1973-74. From the moment Gayoom assumed power, he intertwined Maldivian identity with that of his own, i.e. influenced and shaped by Egyptian culture, outlook, and beliefs. Maldivian Islam was, for the next thirty years, shaped, directed and dictated by Gayoom, the Egyptian graduate.

The Maldivian Constitution of 1968 stipulated Islam as the State religion. In 1997 Gayoom enacted a new Constitution in which he gave the Head of State—then himself—the power to be ‘the ultimate authority to impart the tenets of Islam’. This formalised what had been the status quo since his rule began. The first real challenge to Gayoom’s religious authority, granted to him by a Constitution he more or less drafted, came from the Maldivian Islamic revivalist scholars educated in Pakistan, mostly on scholarships provided by external sources. Several of the returning graduates challenged not just Gayoom’s religious authority but also his right to dictate what form of Islam Maldivians should practise. Gayoom was brutal in his crackdown on the practise of fundamentalist Islam, driving those who practised it to unite against his authority. Adhaalath Party was the result. Since then the party has undergone many changes, and has evolved into the most vocal Islamist party in the history of the country. Its founding members are no longer together, some having left to join the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP) while others have remained with Adhaalath which has, in a volte face hard to fathom, now aligned itself with Gayoom and his People’s Party of the Maldives (PPM). Adhaalath Party’s most successful time came during the first three years of democracy in the Maldives, flourishing in the environment of free expression fostered by President Mohamed Nasheed.

The global roots of Islamism

Changes in religious practises that Maldives has undergone throughout its history have invariably been linked with changing international patterns of behaviour. Islam came, for example, with burgeoning trade on the Silk Route. Portuguese influences that are said to have threatened Maldivian Islam came with the beginning of the European colonisation project. Gayoom brought with him Egyptian Islam at a time when Iran was going through the Islamic Revolution and tension was high between ‘the Arab world’ and ‘the West.’ Islamism arrived with a vengeance as the world began to talk to of a ‘clash of civilisations’ between Islam and the West. In attempting to understand the current religious habits of the Maldivian population, it is helpful to look at what Islamism is, and how it has progressed through history to become the force it is today.

The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism describes political Islam as having emerged in its modern form as a movement against secular pan-Arabism and/or autocrats endorsed by the West. Its objective is to return to a ‘Golden Age of Islam’ where Shari’a is implemented and the State is Islamised at all levels. Intellectual heavy-weights of the movement such as Mawlana Abdul A’la Mawdudi, Sayyid Qutb and Abdulla Azzam shared and propagated the idea that man-made law is tantamount to apostasy and is denotive of Jahiliyya. Osama bin Laden was a great admirer of Qutb’s ideas and thinking. [Incidentally, in his authorised autobiography, Gayoom, too, professes to be a Qutb admirer.] The ideas made popular by Qutb and his contemporaries were, however, not new; they have been around for centuries. Thirteenth Century Salafist thinker Taqi al-Din Ibn Taymiyya floated such ideas during the Mongol Empire’s expansion into the Middle East; Muhammad Ibn Abdul Wahhab, whose thinking engendered what is today known as Wahhabism, propagated similar ideas in the Eighteenth Century; and, Indian Muslim activist Sayyid Ahmed Rei Barelvi did the same in the early Nineteenth Century. Following in their footsteps, Islamist leaders have mobilised resistance against various types of regimes—imperialists, Muslim secularists, autocrats, liberal democracies—that were grappling with a shift from the traditional to the modern. Some analysts have contextualised Islamic fundamentalism as a strand of anti-colonial resistance to European expansion into territories previously held by the Ottoman Empire which began after the Enlightenment. In Al-Qaeda and What it Means to be Modern, John Gray points out, for instance, that Qutb—a leading member of the Muslim Brotherhood—borrows heavily from European anarchism. His ideas were influenced, Gray has noted, by the ‘Jacobins, through to the Bolsheviks and latter day Marxist guerrillas.’ A similar explanation for the phenomenon of Islamism has been offered by French professor Olivier Roy in Globalised Islam: the Search for a New Ummah. Roy asserts that ‘fundamentalism is both a product and an agent of globalisation, because it acknowledges without nostalgia the loss of pristine cultures, and see [as] positive the opportunity to build a universal religious identity, delinked from any specific culture.’

Islamism in the Maldives

Being poor, under-developed and geographically isolated, and lacking in rich natural resources (other than beauty), foreign powers left Maldives pretty much to its own devices for most of modern history. Almost all of the Maldivian population remained oblivious (and a substantial part still does) to ideological changes that re-arranged human life—communism, socialism, Marxism, etc. It remained similarly impervious to changes and evolution in Islamic jurisprudence, ideas and thinking. Life, and faith, was simple. All Maldivians accepted themselves as Muslims and adhered faithfully to its core tenants, principles and values without much ado. There appeared no need to declare one’s ‘Muslimness’, and, apart from Gayoom’s efforts to become the Supreme Leader of Islam, religion and politics remained separate. All Maldivians accepted themselves as Muslims and adhered faithfully to its core tenants, principles and values. The change that Maldives could not remain impervious to, however, came in the form of globalisation in the 1990s.

9 comments