by Azra Naseem

If there is a particular event which can be pointed to as the beginning of the end of Maldives’ peaceful transition to democracy, the acceptance of the 2012 CONI report as a way forward can be described as such. This document, supported and endorsed by the international community, declared the transition of power on 7 February 2012 as legitimate and devoid of wrongdoing. In so doing, it created the conditions for the emergence of the present Maldives: a place of injustice, endemic corruption and, as described by Maldivian writer, Latheefa Ahmed Verall, tragically lacking a moral radar. The CoNI report made it necessary for tens of thousands of outraged democracy supporters to at least be seen to be accepting its findings — in the name of democratic leadership, statesmanship, and stability.

The task ahead for all Maldivians must be to strengthen democracy in the Maldives. An atmosphere of peace and public order is essential for that to happen.

The Commonwealth Secretary General Kamalesh Sharma, said, admiring the CoNI findings.

Those who rushed to endorse CoNI refused to let proof of the Commission’s failures and backroom deals get in the way of the ‘stability’ it promised by getting ‘all sides to remain peaceful’. When Ahmed Saeed (Gahaa) spoke of the many problems with CoNI, his words were made to have no consequence. The call for dialogue—with those who resorted to a coup to overthrow an elected government—drowned out the angry cry for the right to a democratically elected government. It gave authoritarian forces room on international platforms to reiterate its legitimacy repeatedly, borrowing from the CoNI findings: “there was no illegal coercion or intimidation nor any coup d’état.”

It is time to stop questioning the legitimacy of the government. It is time to stop illegal activities and activities that go against generally acceptable social norms,

Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik, the president bearing the Commonwealth seal of approval said when the report came out.

The Commission’s findings are clearly stated. I do not believe there is any room to raise any questions about the transfer of power.

To be able to say that, with the approval of the international community, was the sole purpose of the CoNI exercise. This is very clear from the fact that now, well into the fourth year since the report was published, no one remembers what else CoNI said. The Commission has long since been dissolved, its website taken off the Internet, along with its report. To recall the report’s ignored contents, it called for urgent investigations into allegations of police brutality, reform of Maldives’ democratic institutions including the Maldives Police Service and the Police Integrity Commission, the judiciary and the Judicial Services Commission, the Majlis and the Human Rights Commission. It recommended national reconciliation.

None of this has happened.

There have been changes, yes. The Human Rights Commission and the Police Integrity Commission mentioned in the report were dismantled and new government-friendly/-bought members installed in them. The Judicial Services Commission remains an unequal den of greedy authoritarian loyalists kow-towing to the government and the Majlis. The People’s Majlis itself is now the engine that fuels government power using a heavy majority to draft and pass legislation to serve the very purpose.

Consolidating power in one party, one candidate, one fist.

In legitimising the coup, the CoNI and its report created the space for all that has followed: the continuation of Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik’s presidency beyond even constitutional limits; the reigning in of civil and political rights; the Supreme Court interventions to steal the 2013 election; the browbeating (and the brutal beating) of people into acceptance of the election results as fair; the corruption that bought the Majlis 2014 election; the stifling of the civil society and the pushing out from public space all civil actors and activists; the hijacking of all powers of government by the executive; the authoritarian pivot in foreign policy away from democratic states and organisations; the unsustainable development at the cost of environment, culture and identity; and the blanket lawlessness of everyday life.

A more in-depth look at the current functioning and character of the key institutions CoNI recommended extensive changes to confirms reform has not yet reached even the germination stage as an idea in Yameen’s head.

The Judiciary, Majlis & oversight bodies

The CoNI report said if Maldivians chose stability over rights, it could get the following: a reformed judiciary which ‘enjoys public confidence’. Confidence in the Maldivian justice system has never been as low as it is now. As former JSC member Aishath Velezinee has provided ample evidence for, judicial reform requires nothing short of a return to Article 285 of the Constitution, and a reversal of the Article to its rightful place as a constitutional stipulation that must be abided by, instead of being allowed to remain cast aside as ‘symbolic’.

The CoNI report said if Maldivians chose stability over rights, it could get the following: a reformed judiciary which ‘enjoys public confidence’. Confidence in the Maldivian justice system has never been as low as it is now. As former JSC member Aishath Velezinee has provided ample evidence for, judicial reform requires nothing short of a return to Article 285 of the Constitution, and a reversal of the Article to its rightful place as a constitutional stipulation that must be abided by, instead of being allowed to remain cast aside as ‘symbolic’.

With this evidence in hand, the government must be challenged in its frequent rhetoric that punishment is meted out by ‘courts of justice’ – there are no courts of justice in the Maldives, only ones of political games and vengeance, underpinned by increasingly dogmatic ideologies.

In the almost four years since the CoNI report, courts have been blatantly political, not just stealing elections but also colluding with the government and its majority-led parliament to define, apply, convict and sentence political dissent as ‘terrorism’. It has put people with followers and ambitions for leadership behind bars one after another—Mohamed Nazim the former defence minister and key figure in CoNI’s ’legal transition of power’; former president Mohamed Nasheed; Sheikh Imran Abdulla, leader of Adhaalath Party and one-time supposedly divinely ordained Kingmaker among them. The former Prosecutor General, Muhuthaz Muhsin, too, is behind bars as is the former Vice President Ahmed Adeeb along with other middling Enemies of the President. The government claims these are punishments ordered by courts of law unrelated to the executive. The spin thinly masks these are punishments handed out by groups of men in robes, working alone or in groups, paid for by the government, to punish whom they deem enemies whichever way they wish.

The courts fail in justice not only in political cases but also in assuring the general public a fair society in which to live. The sentencing patterns of the courts are so erratic observers can be forgiven for thinking the various judgements are coming from jurisdictions with different laws and constitutions. Men who murder can walk free of charge while petty shoplifters get dozens of years behind bars; wife-beaters get lighter sentences than pickpockets; and protesting can get indefinite detention at the discretion of a judge. Last year, a magistrate court judge sentenced a woman to death by stoning. The sentence was quickly overturned by the High Court, but not before it exposed the lack of uniformity and ideological unity within the judiciary.

Colluding with the government and the judiciary in denying justice to the people are the constitutional bodies set up to step up when any branches of power fail or misbehave. At present, leaders of this government stand accused—with evidence—of record levels of corruption. US$ 79 million went missing from the Maldives Marketing and Public Relations Corporation (MMPRC) when Vice President Adeeb was leading it (along with the Ministry of Tourism and the Enviornmental Protection Agency, too).

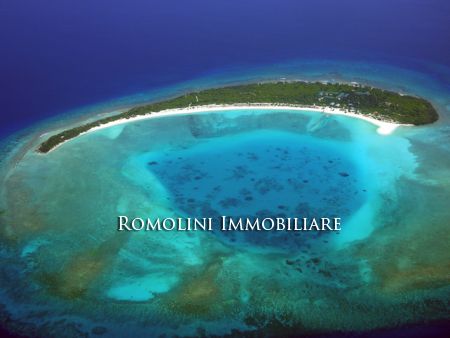

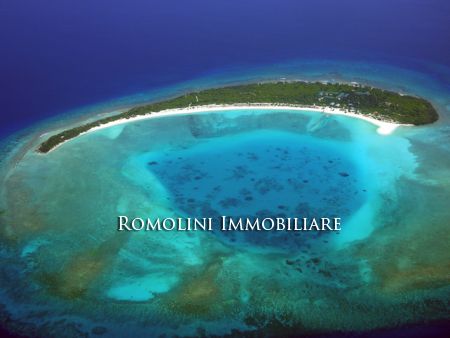

The only natural resources the Maldives has—born of its fragile environment of immense beauty—are being sold rapidly. Reefs, coral gardens, surf spots, diving sites, lagoons, islands gone, bartered away, shut off to the people. The money gained from the sales have been siphoned off in millions, distributed in bundles of dollars, handed out by Adeeb and accepted with grabbing arms by greedy politicians who entered the Majlis on the people’s vote to rob them blind. The government accepts this money is gone from the MMPRC coffers, but has chosen to deal with the matter by saying “the buck stops at Adeeb”.

The only natural resources the Maldives has—born of its fragile environment of immense beauty—are being sold rapidly. Reefs, coral gardens, surf spots, diving sites, lagoons, islands gone, bartered away, shut off to the people. The money gained from the sales have been siphoned off in millions, distributed in bundles of dollars, handed out by Adeeb and accepted with grabbing arms by greedy politicians who entered the Majlis on the people’s vote to rob them blind. The government accepts this money is gone from the MMPRC coffers, but has chosen to deal with the matter by saying “the buck stops at Adeeb”.

The young 32-year-old Adeeb, hoisted onto the peak of political power by Yameen, liked to flash his cash; lived the highlife; loved the limelight; had a weakness for the adoration his money won from women; agreed to everything Yameen wanted and carried out his bidding to the letter. He is now being tried for those same instructions he loyally followed.

No one is independent. Not the judiciary, not the Majlis, not constitutionally mandated independent bodies.

The Maldives Police Service

The Maldives Police Service is another institution the CoNI report highlighted. The MPS has been constantly deteriorating in service and function for the last four years. Their mutiny on 7 February, and the role it played in the change of power is well documented. As is their brutality on 8 February 2012, and on many occasions since.

The Maldives Police Service is another institution the CoNI report highlighted. The MPS has been constantly deteriorating in service and function for the last four years. Their mutiny on 7 February, and the role it played in the change of power is well documented. As is their brutality on 8 February 2012, and on many occasions since.

During Mohamed Waheed Hassan Manik’s caretaker presidency, all that was wrong within MPS was lauded as patriotic national duties. Given the immunity and the impunity with which they were allowed to operate, their abject failure to serve and to protect people today should come as no surprise. Three young men are missing, taken without trace. The high profile case of Ahmed Rilwan remains unsolved, as does the murder of Dr Afrasheem Ali, incidents that disturbed the collective Maldivian psyche. Policelife, an online police magazine, shows numerous activities with puzzling names “Ready Camps” (type and content of courses uknown) targeting adolescent chidlren, awareness classes, futsal lessons, respect camps and other numerous activities that–at least at first glance–don’t have much to do with general policing as such. Trusting there is no hidden agenda is asking for too much given the last four years. When it comes to crime, today it is often hard to separate perpetrator and policeman. Yameen himself accused the police of widespread corruption. His ‘solution’ was to remove then Police Commissioner Hussein Waheed, the fall-guy on this occasion. The allegations remain un-investigated. The buck stopped, as it is designed to do, one step behind Yameen. Since Friday night last week, police are allegedly engaged in gang-warfare — as a warring faction, not as a police force stopping their activities.

There have already been three murders in 2016. The police–if no the entire force than the most powerful parts of it–remain inept, corrupt and, often, brutal.

Governing for stability

Recall what the Commonwealth Secretary General said. In accepting the CoNI report in place of the chaotic fight for democratic rights, what was being created was, “An atmosphere of peace and public order [ ] essential” for strengthening democracy.

It was wrong. Maldives today cannot be any less conducive to democracy. The entire criminal justice system, most of Maldives National Defence Force, and all key independent institutions are under the control of the government, as just discussed. The focus is not on a government of the people, but a government of and by the dollar for the dollar.

At a time when the government should be reeling from not just the millions lost in the MMPRC loot, but also the possible US$900 million price tag on the GMR fiasco, the it remains eager to flash the cash. The government has signed a deal for a US$150 million 25 storey high hospital in Male’ with a swimming pool. It will be built by a Singapore company. A new 25 floor government building is to be constructed in Male’ by a Malaysian company. Together the twin towers are worth US$260 million. Additionally there is the US$210 million China Male’ Friendship Bridge, which has already claimed Male’s beloved surf-spot, Raalhu Gan’du, and a diving site as victims. Numerous other projects continue for a few million here and a billion there. Development without consciousness – measured only by the dollar and the mortar alone – is taking place at breakneck speed.

At a time when the government should be reeling from not just the millions lost in the MMPRC loot, but also the possible US$900 million price tag on the GMR fiasco, the it remains eager to flash the cash. The government has signed a deal for a US$150 million 25 storey high hospital in Male’ with a swimming pool. It will be built by a Singapore company. A new 25 floor government building is to be constructed in Male’ by a Malaysian company. Together the twin towers are worth US$260 million. Additionally there is the US$210 million China Male’ Friendship Bridge, which has already claimed Male’s beloved surf-spot, Raalhu Gan’du, and a diving site as victims. Numerous other projects continue for a few million here and a billion there. Development without consciousness – measured only by the dollar and the mortar alone – is taking place at breakneck speed.

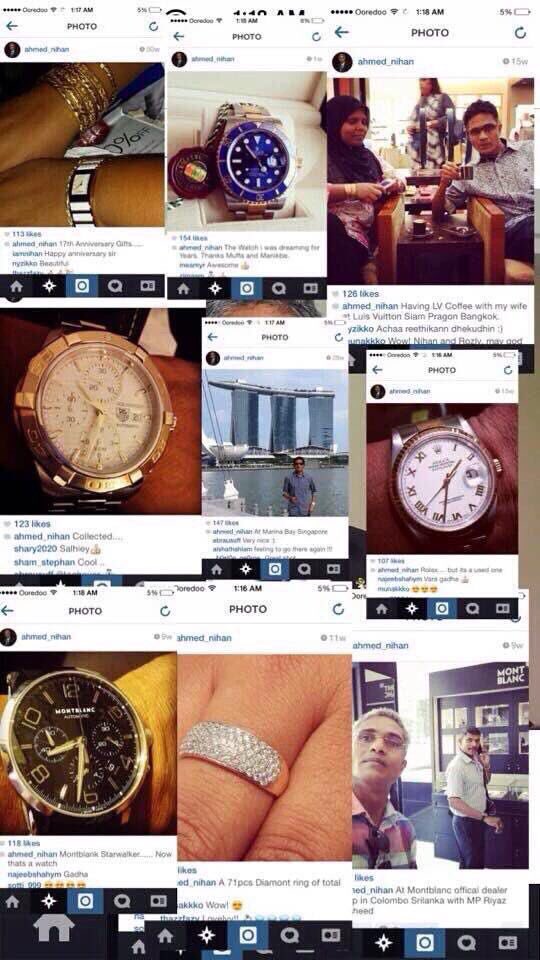

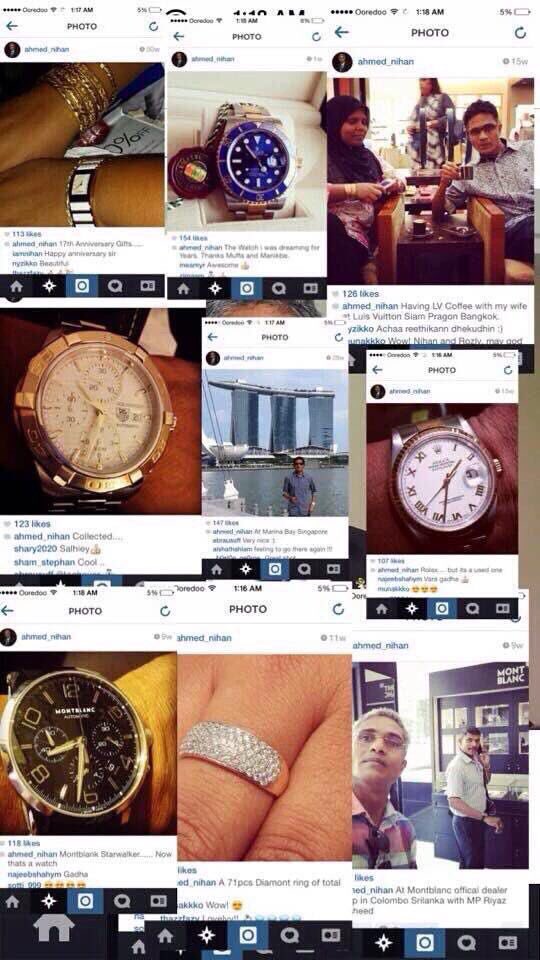

Members of the higher-ranking officials put materialism at the forefront, buying people with cheap diversions and superfluous amusements while they open up the entire country, including its biosphere reserves, for sale. Keep your eyes on the fireworks and LED lights, there is nothing to see here. The government, its so-called ‘elite’ and its faithful followers are bound by a common goal: instant gratification. PPM MPs upload images of their Rolexes, Montblanc pens and BMWs on Instagram and Twitter — brash consumerism as status symbol. They ask why accepting bribes are a problem — what is wrong with paying an MP to be loyal? The President himself is nonchalant, admitting money was distributed. “Who in there right mind, when handed a bag of cash, would ask where it came from?”, he asked.

Members of the higher-ranking officials put materialism at the forefront, buying people with cheap diversions and superfluous amusements while they open up the entire country, including its biosphere reserves, for sale. Keep your eyes on the fireworks and LED lights, there is nothing to see here. The government, its so-called ‘elite’ and its faithful followers are bound by a common goal: instant gratification. PPM MPs upload images of their Rolexes, Montblanc pens and BMWs on Instagram and Twitter — brash consumerism as status symbol. They ask why accepting bribes are a problem — what is wrong with paying an MP to be loyal? The President himself is nonchalant, admitting money was distributed. “Who in there right mind, when handed a bag of cash, would ask where it came from?”, he asked.

The former Auditor General Niyaz Ibrahim who, like Gahaa Saeed, told it like it is, has evidence the rot starts at the top. But, Niayz’s words, like those of others who speak out (Velezinee, Gahaa Saeed, and Fuwad Thaufeek to name some) are being actively unheard, made to be of no consequence.

Meanwhile, science is taking a backseat to the supernatural with Jinnis leading major national security issues; sorcery and black-magic is made government policy; national monuments are moved to ward off evil; and many text books in use work to narrow, not expand, intellectual inquiry. People are paying to have demons exorcised, subscribing to blood letting rituals advertised on Facebook by ‘religious folk’, and going off to war in Syria to escape from the ‘land of sin’. The Supreme Court is taking on international rights bodies, ruling out human rights in the name of Islam and Muslims, openly subscribing to the ideology that Islam and democracy are mutually exclusive.

While strengthening authoritarianism at home, the government has also actively sought to cut ties with western democracy advocates such as the Commonwealth, the UN, Amnesty International, the EU, the UK, the US and several European countries. The President’s Office has been adamant in shouting down the influence of ‘The West’, questioning its right to ‘interfere’ in the ‘internal affairs’ of a democratic Muslim country, meddling in their ‘uniquely small-island’ sovereignty.

The Foreign Ministry’s message is often in discord with Yameen’s, perhaps not without design. Led by niece Dunya Maumoon, the Ministry likes to be a player in western-led international fora, taking the podium to laud Maldivian achievements for women, equality and justice. Standing on the platform of elected legitimacy endorsed by CoNI, government representatives talk democracy, their images photoshopped clean of authoritarianism by highly-paid and mercenary international public relations firms. These representatives whose spoken words have little relation to the reality of their actions at home, take the international stage to lead the world on human rights. They talk about ‘an infant democracy’ with teething problems that needs to be measured by a different yardstick than that applied to established democracies. The source of this hubris is the claim, endorsed by CoNI and the international community, that theirs is a legitimate government in power based on rule of law.

CoNI, Commonwealth, and CMAG

The Maldives is going to be called up to the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG) on 6 April. CMAG is set up to deal with serious or persistent violations of the Commonwealth’s values. The last time they met, on 24 February–despite all the flagrant violations of democratic principles outlined above which all took place in full view of the world–CMAG wasn’t ready to put the Maldives on its agenda. Instead it gave the government around 40 days in which to bring about changes that have already been asked for and wilfully ignored for almost four years. Dunya Maumoon said it was ‘an endorsement of President Abdulla Yameen’s policy on democracy consolidation‘, and she has a point.

The Maldives is going to be called up to the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG) on 6 April. CMAG is set up to deal with serious or persistent violations of the Commonwealth’s values. The last time they met, on 24 February–despite all the flagrant violations of democratic principles outlined above which all took place in full view of the world–CMAG wasn’t ready to put the Maldives on its agenda. Instead it gave the government around 40 days in which to bring about changes that have already been asked for and wilfully ignored for almost four years. Dunya Maumoon said it was ‘an endorsement of President Abdulla Yameen’s policy on democracy consolidation‘, and she has a point.

Yameen boasted shortly after the CMAG decision that his influence on India and Pakistan before the February meeting had secured their cooperation in stopping CMAG from taking action against the Maldives. This shows India as committed to continuing its support for stability over democratic rights in the Maldives. It’s a continuation of the same policy which allowed the instalment and subsequent legitimisation of Waheed as President via CoNI.

According to the CMAG statement, these weeks have been given to the Maldives to seek reconciliation and pursue multiparty dialogue “led by the Government with democratic will” that should be “inclusive, purposeful, time-bound and forward-looking”. Fact is, there is no democratic will in those currently governing the Maldives; nothing inclusive, purposeful, or forward looking in its policies. Government officials speak of ‘annihilation of the opposition’, ‘their destruction’ not of non-partisan political dialogue inclusive of different opinions. To give the Maldives a few weeks in which to magically bid this democratic will out of nowhere is an exercise which serves no purpose. Except perhaps give government officials time to lobby necessary countries and grease some palms before the April meeting. CMAG in this instance was described as ‘toothless’ even by the Commonwealth’s own Human Rights Initiative which recognised democratic transition in the Maldives has long since ground to a halt and is not tottering along at a suitably infant pace as many claim.

The Maldivian democracy movement, and its society in general, did not arrive at this state of affairs all by itself. It was directed to this route and guided along it by the international community which, when dealing with the Maldives in times of coup d’état, put stability before everything else, including the principles of democracy.

This is not to say CoNI is to blame for everything wrong with Maldivian governance today, but to say that its findings made possible the conditions in which the current authoritarian regime could be legitimised. In doing so, it helped bring about–in the name of democracy–an end to Maldives’ first attempt at democratic transition.

Will CMAG hinder or help Maldives democracy on 6 April?

CoNI & the Coup 1: Constructing the truth

CoNI & the Coup 2: Law as an instrument of political power

Photos 1, 2 and 4 from this dying regime | Photo 3 Romolini Estate Agency | 5 & 6 social media, source unknown | 7 Own

The only natural resources the Maldives has—born of its fragile environment of immense beauty—are being sold rapidly. Reefs, coral gardens, surf spots, diving sites, lagoons, islands gone, bartered away, shut off to the people. The money gained from the sales have been siphoned off in millions, distributed in bundles of dollars, handed out by Adeeb and accepted with grabbing arms by greedy politicians who entered the Majlis on the people’s vote to rob them blind. The government accepts this money is gone from the MMPRC coffers, but has chosen to deal with the matter by saying “the buck stops at Adeeb”.

The only natural resources the Maldives has—born of its fragile environment of immense beauty—are being sold rapidly. Reefs, coral gardens, surf spots, diving sites, lagoons, islands gone, bartered away, shut off to the people. The money gained from the sales have been siphoned off in millions, distributed in bundles of dollars, handed out by Adeeb and accepted with grabbing arms by greedy politicians who entered the Majlis on the people’s vote to rob them blind. The government accepts this money is gone from the MMPRC coffers, but has chosen to deal with the matter by saying “the buck stops at Adeeb”. The Maldives Police Service is another institution the CoNI report highlighted. The MPS has been constantly deteriorating in service and function for the last four years. Their mutiny on 7 February, and the role it played in the change of power is well documented. As is their brutality on 8 February 2012, and on many occasions since.

The Maldives Police Service is another institution the CoNI report highlighted. The MPS has been constantly deteriorating in service and function for the last four years. Their mutiny on 7 February, and the role it played in the change of power is well documented. As is their brutality on 8 February 2012, and on many occasions since. At a time when the government should be reeling from not just the millions lost in the MMPRC loot, but also the possible US$900 million price tag on the

At a time when the government should be reeling from not just the millions lost in the MMPRC loot, but also the possible US$900 million price tag on the  Members of the higher-ranking officials put materialism at the forefront, buying people with cheap diversions and superfluous amusements while they open up the entire country, including its

Members of the higher-ranking officials put materialism at the forefront, buying people with cheap diversions and superfluous amusements while they open up the entire country, including its  The Maldives is going to be called up to the

The Maldives is going to be called up to the